NEW DELHI: Given rising bilateral tensions, Beijing and Washington are both trying to consolidate their relationship with other important countries. China receiving Russia’s Foreign Minister Lavrov just prior to the former’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi, embarking on a tour to the Middle East exemplifies this. The efforts have gained momentum after the meeting between Chinese Politburo member Yang Jiechi and Foreign Minister Wang Yi and U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan at Anchorage, Alaska, earlier this year.

The 90-minute meeting did not go as well as China had hoped though, in keeping with China’s uncompromising stance on foreign policy issues, Yang Jiechi appeared to have come with a prepared text to give Blinken a dressing down.

China’s recent moves in Africa, the Gulf and the Middle East point to efforts to build a constituency at this time of serious tension with the US. Wang Yi’s visit to Tehran has come under special focus because of the ongoing tension between the U.S. and Iran and because it coincides with the talks in Vienna to revive Iran’s compliance with the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). Although Beijing has urged the Biden administration to rejoin the JCPOA, which regulate Iran’s nuclear activities, the visit by Wang Yi at this juncture potentially provides China an opportunity. Especially the signing of the long speculated 18-page, 25-year “strategic partnership” deal between the two countries, not only ensured global attention to his visit to Tehran, but reveals China’s underlying ambition to increase influence in the region. An opinion published by state-owned China Global Television Network (CGTN) on March 29 endorsed this. It said that the China-Iran deal would “totally upend the prevailing geopolitical landscape in the West Asia region that has for so long been subject to U.S. hegemony”.

Though the Middle East has not been a priority on China’s foreign policy agenda, its interest in Iran stretches back to February 1979 when it quickly recognised the new Islamic regime and began assisting it to develop its military—and clandestinely—its nuclear capabilities. China was careful, however, not to get involved in the Iran-Iraq War although it had ties with both sides. It was similarly careful not to antagonise either the U.S. or Israel as it was trying to improve relations with both.

Since mid-2010, China has reduced and restricted economic interactions with Iran largely because of pressure from the United States. Following a series of UN and multilateral sanctions restricting financial dealings with Iran’s central bank, China curtailed its imports of oil and gas from Iran. Beijing, however, kept up relations with Tehran and Iran was admitted into the Shanghai Cooperation Organization as an ‘observer’ in 2005. China scholars described policy towards Iran as “actively expanding China’s circle, within international norms, to not only gain the benefit of overseas energy supplies but also to protect China’s overseas financial interests in the United States and elsewhere.”

On March 26, Wang Yi and Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif signed the China-Iran Strategic Comprehensive Agreement expressing a desire to increase cooperation and trade over the next 25 years. The signing of the agreement was aired live on state-run TV. However, the text of the agreement has not yet emerged and is unlikely to be published although a draft was leaked last summer. The 25-year deal has the potential to give China enhanced influence with Iran and in the region.

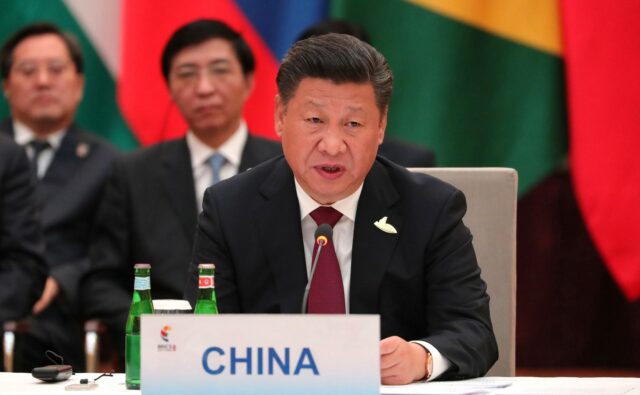

The deal has been under negotiation since 2016 when President Xi Jinping visited Tehran. Javad Zarif has also visited China numerous times in recent years, testifying to the high importance that Tehran attached to the negotiations that culminated in the formal signing of the deal on the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between the two countries.

The New York Times had in 2020 reported on a draft version of the agreement, which it claimed envisaged Chinese investments totalling US $400 billion! The report said the deal would include a wide range of sectors spanning energy, banking, telecommunications and infrastructure. It would also offer military cooperation, including joint training, as well as research and cooperation in their defence industries. The New York Times said that, in return, China would receive heavily discounted supplies of Iranian crude oil for the next 25 years.

This is the first time that Iran has signed such a lengthy agreement with a major world power. By doing so, Iran hopes to balance Washington by building closer ties with China. The agreement also offers significant benefits to China. By anchoring itself in the region, China aims to integrate Western Eurasia—as Beijing calls it—deeper into its Belt and Road Initiative.

The day after the signing, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Zhao Lijian said the agreement “neither includes any quantitative, specific contracts and goals nor targets any third party, and will provide a general framework for China-Iran cooperation going forward.” On the Iranian side, Foreign Ministry spokesman Saeed Khatibzadeh said the agreement was a “road map” for trade and economic and transportation cooperation, with a special focus on both countries’ private sectors. Chinese investments in Iran’s energy and infrastructure sectors were expected. Following criticism regarding why the details of the agreement were not published, the Foreign Ministry’s Assistant for Asia-Oceania Affairs, Reza Zabib, claimed that it was “not customary” to publish agreements that were “unenforceable”. The agreement is yet to be presented to Iranian Parliament.

While the agreement is likely to lead to increased investment and linkages between the two countries, it can best be described as an aspirational document. No specific commitments have been made, no figures mentioned, and no indication given of unprecedented military cooperation or Chinese troops being stationed in Iran. Rather, the agreement appears to be a roadmap with general plans for cooperation in ventures in areas ranging from banking and mining to infrastructure and space exploration between banks and infrastructure projects related to the “New Silk Road” and the Belt and Road Initiative. A major gain for Wang Yi personally and possibly for China was the official Chinese news agency Xinhua’s report on March 28, that Tehran had expressed interest in signing on to Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) projects and other projects in the region, with possible finance from Chinese banks.

Iran sees China as a vital lifeline for its economy that has been weakened by sanctions and diplomatic isolation. The partnership with China— its top oil importer—gives Iran a stable market for oil, allowing it room to posture and negotiate, especially with regard to resuming the nuclear deal with the U.S. The Diplomat stated that after eight years of courting the West with nothing to show for it, China represents a change of course for Iran—whether as a potential new partner or as a “China Card” to leverage in negotiations with the U.S. Former Iranian diplomat and columnist for several Iranian newspapers, Fereydoun Majlesi observed that “Every road is closed to Iran. The only path open is China. Whatever it is, until sanctions are lifted, this deal is the best option.”

If implemented, Iran will be able to break the wide-ranging Western sanctions embargo—which estimates claim has cost it almost half its oil exports, a large drop in GDP, and sharp rise in the cost of living—by supplying oil and gas to China. In the press releases announcing the agreement, Beijing also indicated its willingness to invest in “the up-and-downstream projects of the energy industries” in Iran. This conforms to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s leadership’s keen interest in securing reliable, long-term supplies of oil from the Middle East. According to the South China Morning Post (April 3) Wang Yi also tried to erode “petrodollar hegemony” by persuading his Middle Eastern hosts to accept oil payments in renminbi.

While the deal has significant support among Iran’s business community and at multiple levels of government, others do not consider China a stable partner, since it has pulled out of many deals with Iran in the past. China’s track record of actual investments in various countries is barely six per cent of the committed amounts. Closer relations with China also remain unpopular with segments of the Iranian population who are often reluctant to buy Chinese goods because of their perceived lower quality.

The official Fars News agency described the agreement as “somewhat ambiguous, …. with pros and cons.” Regarding technology transfer, it urges that “if Iran wants to make progress… it should not wait for the other side” and needs to develop “a long-term plan” before entering into specific agreements. It says that while Chinese investors are “encouraged” to invest in Iran’s various free economic zones, such as along the Turkish border, on an island in the Strait of Hormuz, and in a strategic Free Zone near Shatt al-Arab, the infrastructure that exists has not “been able to actively attract even domestic investment”. Former President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, in a speech in late June, called it a suspicious secret deal that the people of Iran would never approve.

Meanwhile, rumours on social media say that the deal will lead to nuclear waste being dumped in the desert and islands in the Gulf being sold to China. Others claim that Iran will be flooded with Chinese workers and crime-ridden Chinatowns.

An Iranian news agency reports that protests broke out in Tehran, Karaj, and Isfahan against what they perceive as selling out their country to China. Social media showed people chanting “Iran is not for sale” outside parliament, while in Isfahan signs said, “China get out of Iran” and “We want the 25-year agreement cancelled.” Wall graffiti also denounced the accord.

Unconfirmed sources wrote that China will invest $280 billion in Iran’s oil and gas industry, and $120 billion in Iran’s transportation industries. In exchange, Chinese projects will be prioritized, and 5,000 Chinese soldiers will be sent to Iran to oversee the “security” of their projects.

Considering China’s plans for projecting power—especially maritime power—in the Indo-Pacific and beyond, cognisance needs to be taken of reports leaked by senior sources close to the Iranian government to OilPrice.com in early September 2020. These claim that China could seek to build an espionage hub In Iran under the 25-year deal. They state that electronic espionage and warfare capabilities would be centered around the port of Chabahar. In their estimation, in 25 years Iran will be an irreplaceable geographical and geopolitical fulcrum of Beijing’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ project.

OilPrice.com also cited these sources as saying that China planned to use the end of the global arms embargo on Iran on October 18, to fast-track preparations for its increased military presence in Iran as part of the ‘China-Iran Integrated Defence Strategy’. One of its priorities will be to ensure that the military hardware and personnel that China, and Russia would deploy in Iran are not vulnerable to attack. To protect Chinese and Russian firms working in Iran despite the U.S. sanctions, counter-measures to be deployed would include three key EW areas namely, electronic support (including early warning of enemy weapons use); electronic attack (including jamming systems); and electronic protection (including of enemy jamming). Iran will host a range of Chinese and Russian technology, equipment, and systems for proactive intelligence-gathering. The defensive equipment will include Russia’s S-400 anti-missile air defense system and the Krasukha-2 and -4 systems. The report claimed that dual-use facilities will be built next to the existing airports at Hamedan, Bandar Abbas, Chabahar and Abadan and that dual-use facilities will be created at Iran’s key ports of Chabahar, Bandar-e-Bushehr and Bandar Abbas. At Chabahar port, China plans to build one of the world’s largest intelligence gathering listening stations with a staff of nearly 1,000, and a near-5,000 kilometre radius range.

Whether China genuinely intends to fulfil these expectations, or do just enough to ensure its oil supplies and get ports to extend the operational reach of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Navy warships, is uncertain. It is definite, however, that many countries will keep China’s activities in Iran under very close watch especially as its ports are close to the Gulf of Oman and the Strait of Hormuz. Beijing will need to tread carefully as any sign of Chinese military-related activity or joint Russian-Chinese activity will invite a sharp and swift response.

(The author is former Additional Secretary, Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India and is presently President of the Centre for China analysis and Strategy (CCAS). He is also a Distinguished Fellow with the Centre for Air Power Studies (CAPS). Views expressed in this article are personal.)