The bounty of HK $1 million each announced July 3 on the heads of eight pro-democracy activists living abroad by the Hong Kong police has sparked howls of protest from western capitals.

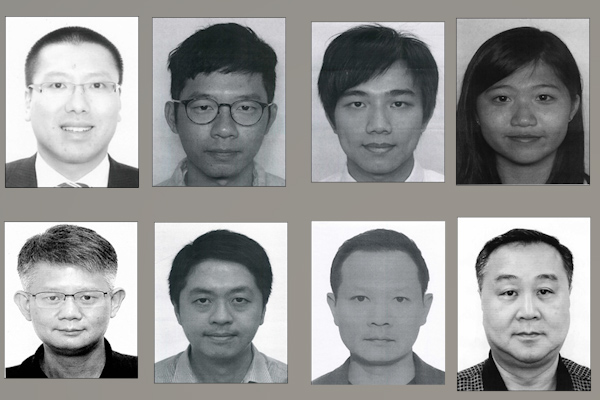

The activists — seven men and one woman, aged between 26 and 74 — left Hong Kong during and just after the 2019 pro-democracy unrest, and now reportedly live in Australia, Canada, the United States and Britain, and some have even taken up citizenship in these nations.

Beijing crushed the unrest before imposing the stringent national security law, which defines and bans all acts of terrorism, secession, subversion, and collusion with foreign forces, and lists stringent punishments including death for violators, in June 2020. The law reportedly claims jurisdiction over any person of any nationality who has committed any of the offences under its purview, anywhere in the world.

The police said the crimes committed by the eight include calling for sanctions against Chinese political repression in Hong Kong, which the national security law classifies as “subversion of state power”, an offence punishable by life imprisonment.

“Quite a few called for sanctions against judges and prosecutors, undermining the well-established, uninterrupted power of judges,” and “some even proposed to foreign countries how to attack the financial system in Hong Kong,” a senior police official said, and asserted that law enforcement agencies would continue to cut off the fugitives’ alleged criminal proceeds, their source of funding and identify their accomplices in Hong Kong.

On July 4, Hong Kong chief executive John Lee said those absconding would be pursued for life, and the only way for the activists to “end their destiny of being an absconder who will be pursued for life is to surrender.”

The eight people charged include former pro-democracy lawmakers Nathan Law Kwun-chung, (watch an exclusive interview in the links below) and seven others. While the move certainly has intimidation value, the fact remains that most western nations suspended extradition agreements with Hong Kong after the promulgation of the national security law in 2020. However, the risk of extradition cannot be ruled out by nations which have friendlier ties with Beijing, or those where Beijing wields economic or political influence.

Within hours of the bounty being announced, US State Department Spokesperson Matthew Miller responded.

“The United States condemns the Hong Kong Police Force’s issuance of an international bounty for information leading to the arrest of eight pro-democracy activists who no longer live in Hong Kong. The extraterritorial application of the Beijing-imposed National Security Law is a dangerous precedent that threatens the human rights and fundamental freedoms of people all over the world,” he said in a statement.

“We call on the Hong Kong government to immediately withdraw this bounty, respect other countries’ sovereignty, and stop the international assertion of the National Security Law imposed by Beijing. We will continue to oppose the PRC’s transnational repression efforts, which undermine human rights. We support individuals’ rights to freedoms of expression and peaceful assembly,” it concluded.

“Canada is gravely concerned by the issuance of arrest warrants by Hong Kong authorities for eight democracy activists around the world,” said a statement issued by Charlotte MacLeod, a spokesperson for Global Affairs Canada, which manages Canada’s diplomatic and consular relations. “This extraterritorial application of the National Security Law further silences peaceful dissent and undermines protected rights and freedoms guaranteed under Hong Kong’s Basic Law,” she said.

Australian foreign minister Penny Wong said “freedom of expression and assembly are essential to our democracy, and we will support those in Australia who exercise those rights. Australia remains deeply concerned by the continuing erosion of Hong Kong’s rights, freedoms and autonomy.”

“It’s just unacceptable,” added Prime Minister Anthony Albanese in a television interview July 5. “We will continue to cooperate with China where we can, but we will disagree where we must. And we do disagree over human rights issues.”

In London, Foreign Secretary James Cleverly declared that his government “will not tolerate any attempts by China to intimidate and silence individuals in the UK and overseas”.

Nathan Law, one of those on the Hong Kong list who’s been granted asylum in the UK, told the BBC that the bounty meant he would have to be more vigilant, since “there could possibly be someone in the UK – or anywhere else – to provide information of me, for example, my whereabouts, where they could possibly extradite me when I’m transiting in certain countries.”

“British politicians have openly offered protection for fugitives,” said the Chinese embassy in London. Describing it as a “crude interference in Hong Kong’s rule of law and China’s internal affairs,” the embassy demanded that British politicians “stop using these anti-China Hong Kong disruptors to jeopardise China’s sovereignty and security”.

Back in Hong Kong, a pro-Beijing tabloid compared the government’s bounty with those issued by the American FBI for wanted terrorists, and said “the sauce that is good for the goose is good for the gander.”

Related stories:

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.