NEW DELHI: Ananth Krishnan, journalist and author, had a question for the tweeple on Monday: Why did Ram Madhav delete his tweet?

The tweet in question ran thus: “Attended d funeral of Coy Ldr Nyima Tenzin, a Tibetan who laid down his life protecting our borders in Ladakh, and laid a wreath as tribute. Let d sacrifices of such valiant soldiers bring peace along d Indo-Tibetan border. That will be d real tribute to all martyrs.”

Nothing objectionable it would seem. And Ram Madhav has all the right credentials; he remains a BJP functionary who holds no government post. But something prompted Madhav to delete his tweet. In the absence of any comment from him, speculation took another direction. Was he advised to delete it, perhaps by somebody in government?

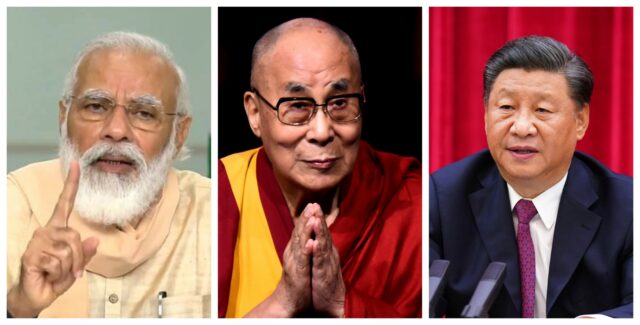

If that is the case, it underscores a widely held view that India remains overly sensitive to China, seeing a need to play down anything that could provoke a rebuke from Beijing. Some China scholars point to a government order two years ago, banning its officials from attending ceremonies marking 60 years of the Dalai Lama’s exile in India. Ironically, this came after India had stared down China on Bhutan’s Doklam Plateau.

Others say India has played hot and cold: in 2014, Sikyong Lobsang Sangay was invited to Narendra Modi’s inauguration as prime minister, but the latter has reportedly met the Dalai Lama only once, in 2014 ahead of President Xi Jinping’s visit; yet the Tibetan spiritual leader was given permission to visit Arunachal Pradesh in 2017; again key officials such as the national security adviser have also met the Dalai Lama but on very few occasions; sentiment in the Ministry of External Affairs seems firmly against giving the exiled Tibetans and their leadership any room for manoeuvre.

China watchers in India admit that none of this amounts to anything really substantive. Meeting or not meeting somebody does not amount to strategy, which is probably what is missing in India’s China/Tibet policy. There does not appear to be any grand vision underpinning India’s strategy towards China. We remain largely reactive, waiting for the next crisis that Beijing provokes, to respond, as is the case now in Ladakh.

The overwhelming effort seems to play down any Chinese provocation and find excuses for Beijing’s conduct. The difference this time, however, was the public anger triggered by the killing of 20 army personnel by the Chinese in June. Overnight, it seemed, India’s low-profile-not-daring-to-offend-China- policy had collapsed. It looked even worse given the number of times Narendra Modi and Xi Jinping have met since 2014, that included two informal Modi-Xi summits besides other meetings. China had stabbed India in the back again, ignoring key treaties it has signed designed to ensure tranquility on the Line of Actual Control. It underscored an uncomfortable point: India’s tendency to lie low (Doklam may have been seen as an aberration) in the face of extreme Chinese provocation over many years, may have given the Chinese the confidence to do what they did in the Galway Valley in June.

The weakness in this argument is that India’s “lie low policy” was driven by the awareness of our lack of economic and military capability and, therefore the need to build it up, which takes time. Even if one accepts that India’s done a poor job of building that capability, it’s no less true that since 1962, whenever China attempted to force an armed solution on India, it failed. This happened in Nathu-La in 1967 and again in Sumdorong Chu in Arunachal Pradesh in 1986. Add to that, Chinese transgressions in Ladakh have increasingly been blocked or countered as infrastructure on the ground improved.

Cut to the present. The government is working on a twin-track approach: try and resolve the standoff through negotiations but also preparing for a short, swift skirmish. The decision to move into hitherto unoccupied heights in the Chushul sector on 29-30 August, surprising and embarrassing the Chinese, is part of this strategy. Wherever possible, militarily, creep forward and keep the Chinese guessing even as diplomatic engagement continues at the highest level. EAM Jaishankar’s likely meeting with his counterpart Foreign Minister Wang Yi will provide some answers to the question: what next? Will the Chinese withdraw? Or will the standoff extend well into winter?

But even if the Chinese withdraw, what happens tomorrow? China has shown contempt for agreements negotiated at the highest levels of the government. So could it be a case of both sides withdrawing but India retaining some presence across the entire expanse of eastern Ladakh to ensure the PLA doesn’t attempt another bash and grab? Then why stop at Ladakh? Arunachal Pradesh and the Central Sector are equally vulnerable. So could the LAC end up like another LoC? Waiting for answers.

Thirty eight years in journalism, widely travelled, history buff with a preference for Old Monk Rum. Current interest/focus spans China, Technology and Trade. Recent reads: Steven Colls Directorate S and Alexander Frater's Chasing the Monsoon. Netflix/Prime video junkie. Loves animal videos on Facebook. Reluctant tweeter.