A three-day event titled “Spirit of Tibet: Celebrating Culture and Compassion” at the India International Centre in Delhi, was an opportunity to mix Tibet’s rich cultural heritage and historical significance with some issues of strategic salience.

There were Tibetan cultural performances and discussions on politics and spirituality. These were showcased in the context of Tibet’s historical journey, with exhibits and artefacts, followed by screening of documentaries and films. Those of a different bent can sample Tibetan medicines or explore Tibetan astrology.

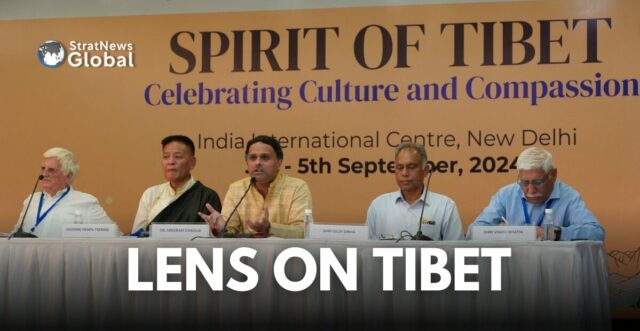

Inaugural Session: “Relevance of Tibet to India”

But a discussion featuring Penpa Tsering, head of the Central Tibetan Administration, former diplomat Dilip Sinha whose recent book Imperial Games in Tibet is garnering appreciation and acclaim, also celebrated Tibetologist Claude Arpi and Lt Gen Viinod Bhatia, ex-DG Military Operations, drew a packed house.

With the focus on the Relevance of Tibet to India, Penpa Tsering confirmed an ongoing collaboration with the US to challenge China’s spurious claims to Tibet. “We intend to convince more countries to challenge Beijing’s narrative,” said Tsering.

Ambassador Sinha highlighted the strategic shift along the India-Tibet border, saying, “There was a time when the India-Tibet border was considered the most secure, but now that it is the India-China border, it has become a security nightmare for us.”

The “Six Wars” China May Fight

Gen Bhatia underscored an important point: while younger generations may have forgotten the 1962 India-China border war, the Galwan clash has revived memories of that tragic conflict, shaping a view of China which is watchful and wary

He referenced a theory predicting that China could engage in six major conflicts over the next several decades to restore what it perceives as its historical glory. These potential conflicts reflect China’s aggressive approach to territorial expansion:

- Unification of Taiwan (2020–2025): China considers Taiwan’s unification non-negotiable and reserves the right to use war to realise its aims

- Recovery of South China Sea Islands (2025–2030): After a possible victory in Taiwan, China may shift focus to asserting control over the disputed South China Sea islands, even though those claims are not tenable under the UN Laws of the Seas.

- Reconquest of Southern Tibet (2035–2040): Arunachal Pradesh, which China calls Southern Tibet, remains a contested area. The long-standing McMahon Line border dispute between India and China makes this region a focal point for China’s aggression.

- Conquering Diaoyu and Ryukyu Islands (2040–2045): China aims to reclaim these Japanese-controlled islands, citing historical ties. The islands are currently under Japanese control.

- Invasion of Mongolia (2045–2050): China views “Outer Mongolia” as part of its historical territory and may seek to assert control over it, following similar patterns seen in its territorial disputes elsewhere.

- Reclaiming Land from Russia (2055–2060): China may eventually focus on regaining land lost to Russia, seeking to Siberia it believes was historically part of China.

China’s Long-Term Strategic Approach

Bhatia summarised China’s expansionist strategy with the formula: “claim, occupy, legitimise, impose, exploit, and integrate.” He stressed that China operates with a long-term vision, aiming to solidify and legitimise its territorial claims over time. In contrast, he suggested, India sometimes overlooks the deeper historical context.

He also explored the evolution of terminology around the India-China border, noting how the Indo-Tibet border was gradually rebranded into what is now called the Line of Actual Control (LAC). He emphasised that this rebranding, particularly the shift from the 1970s onwards, reflects China’s strategic influence on regional perceptions.

The “Line of Perceptions” and the Complexity of the LAC

Bhatia offered an interpretation of the LAC, describing it as more than just a physical border. He described it as a “Line of Perceptions,” comprising four distinct lines:

- India’s Perception of the LAC: How India defines the boundary.

- China’s Perception of the LAC: How China views the boundary.

- India’s Perception Based on China’s View: India’s understanding of the boundary, influenced by China’s positioning and claims.

- Combined Perception: A mix of both Indian and Chinese interpretations of the LAC.

“The LAC, if I may put it as Line of Perceptions. It is not one line, it is not two lines, it is not three lines but four lines,” he explained, underscoring the complex nature of this dispute.