NEW DELHI: Unmindful of all the doom scrolling in mainstream media, Morgan Stanley last week put out a report on India that was not merely optimistic. It was a hosanna. Their outlier claim is that the next decade is India’s for the taking.

“The four global trends of Demographics, Digitalization, Decarbonization and Deglobalization are favouring the New India.

We estimate The New India will drive a fifth of global growth through the end of this decade.”

Wow!

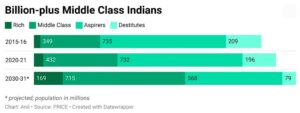

Separately, a survey conducted by People’s Research on India’s Consumer Economy and Citizen Environment (PRICE) released last week claimed that in this period the country’s middle class will balloon from the present level of 432 million to 715 million by 2030-31—an increase of 65.5 per cent.

Seems logical given that the United Nations Development Fund (UNDP) just disclosed that India lifted a staggering 415 million people out of poverty, suggesting a key cohort of the country’s populace is trading up.

Connect the dots and the picture of emerging India is not just one which is flattering. Instead its significance lies in the fact that it is one which is immensely transformational. A makeover of this scale has been witnessed only once before with respect to China.

Needless to say this will force an unprecedented socio-economic transformation of India, resolving a bulk of its legacy problems and acquiring new and unfamiliar warts as it wades into uncharted territory. At the least it will trigger a reset in the country’s polity, some of which is already visible.

Up, Up and Away

Like I pointed out in the introduction, Morgan Stanley believes the next decade, based on the strong foundations that have been put in place in the last 10-15 years, will witness an explosion in India’s growth.

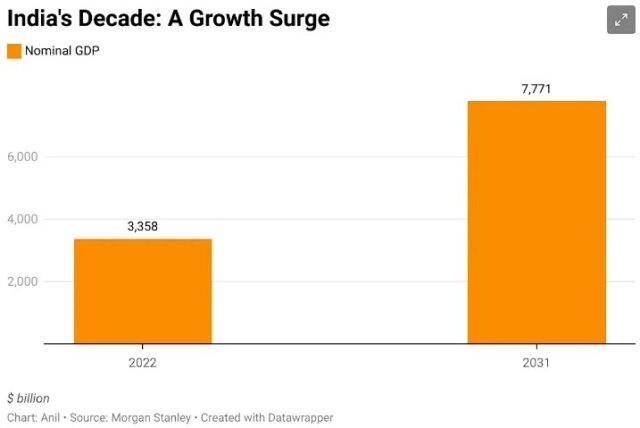

As the graphic above shows, India’s gross domestic product in nominal terms will grow from its present level of $3.3 trillion to $7.7 billion. This is a staggering growth projection. India will grow its economy by about $4.5 trillion in this decade—which is more than how much it grew in its first 75 years.

Morgan Stanley’s optimism about India is premised on three beliefs:

- Offshoring: The ongoing geopolitical reset entailing decoupling of the West with China has opened up the possibility of India emerging as the factory of the world. This trend has got a leg-up with the recent round of reforms, including record reduction in corporate tax rates, and the Production Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme.

- Digital Differentiation: The digitalisation of the Indian economy is being powered by a unique homegrown India tech stack. It is reinventing the way India consumes, lends and trades at scale.

- Energy Transition: The way India sources energy and consumes it is happening simultaneously. In short the increase in consumption will be powered by green energy, implying that legacy fossil-based power capacity need not be destroyed. It will also reduce India’s dependence on imported energy.

And for those of us who rightly worry about per capita income, Morgan Stanley has news. It will grow from its present level of $2,393 to $5,140 in 2031.

According to the financial services company, this will trigger a boom in discretionary consumption and a surge in stock market capitalisation to $10 trillion.

The Middle Class Rises

Implicit in this bright future of India projected by Morgan Stanley is one key variable: the middle class.

This cohort is driven by aspirations, spends, saves, invests and is very aware of its political rights. As a result, the middle class, even though it is not homogenous, has always been viewed as a key economic agent in the transformation of an economy.

Way back in 2007—when there was similar optimism about India—McKinsey Global Institute had zeroed in on the emerging middle class to argue that they would power the country’s consumer economy. But, India only flattered to disappoint.

However, the aspiration quotient of the Indian middle class kept growing. A nation-wide survey conducted by Carnegie Endowment, a U.S.-based think tank, found that one in two people self-identified themselves as middle class even though their material conditions did not warrant it.

“We find that almost half of all respondents we surveyed across India identified themselves as part of the middle class. While there is substantial variation across states, which is not altogether surprising, identification is stronger in urban areas when compared to rural ones.

However, middle class identification is broad-based, spanning all income groups and educational strata. While there is an almost linear correspondence between income/education and middle class affinity, what is striking is not necessarily the difference between groups but the consistency across them.

When it comes to social aspiration and economic optimism, there is a distinct middle class positivity on both counts.

Statistical analyses suggest that middle class self-identification accounts for a good deal of the variation in economic optimism and social aspiration that is not attributable to either income or education.”

The recent research published by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) about India lifting a record 415 million out of poverty in 16 years ended 2021 only suggests that the country’s middle class would have grown.

According to the study published by PRICE, the middle class (the segment which earns an annual income of Rs5-30 lakh) is 432 million in 2020-21—it was 349 million in 2015-16.

This cohort is projected by PRICE to top 1 billion by 2047, creating an unprecedented bulge in the middle demography.

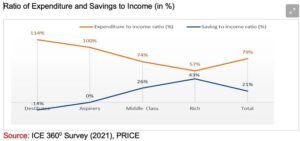

And the economic significance of this expansion in the middle segment is reflected in the graphic below shared by PRICE.

While the aspirer class (annual income of Rs1.25-5 lakh) saves little or nothing, those at the bottom of the pyramid are in a debt trap.

However, the middle class clearly enjoys surplus income, which it saves/invests.

Proxy data like the one on demat accounts—tripling in the last three years to 100 million—surge in consumption of FMCGs, big burst in domestic and international travel, suggest that the middle class is growing rapidly and powering the consumer economy.

At the moment their aspirations exceed their earnings. But, as the Morgan Stanley report suggests, it is only a matter of time before aspirations catch up as the economy swings into a new growth path.

In the final analysis it is clear that India’s future is bright. This is welcome news for 1.3 billion Indians, who have spent most of the last 75 years looking in from the outside. Their participation in the Indian economy will not only mean inclusion, but will also lend unprecedented vitality and dynamism.

Needless to say, India’s rise augurs well for the world too.

(The author is a columnist and hosts a weekly show called ‘Capital Calculus’ on StratNews Global. Views expressed in this article are personal.)