NEW DELHI: After a 10-hour vigil in March this year, British warship HMS Montrose that was on patrol in the Arabian Sea intercepted a dhow off Oman, leading to recovery of nearly three tonnes of heroin, crystal methamphetamine and hashish. The frigate had reported two back-to-back seizures in mid-February, confiscating a range of illegal narcotics worth US $15 million. In December last year, U.S. Navy’s guided-missile destroyer USS Ralph Johnson intercepted over 900 kilograms of narcotics from a stateless dhow operating in the Arabian Sea. USS Ralph Johnson, like HMS Montrose, was deployed in support of Combined Maritime Forces (CMF), the international partnership for maritime security in the Western Indian Ocean, and her success marked the fourth CMF narcotics seizure since October 2020.

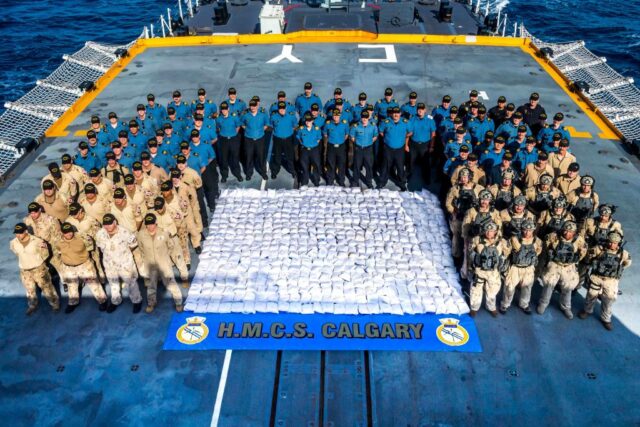

The bigger honour for the largest drug haul in CMF history, however, was clinched by Canadian warship HMCS Calgary in April this year, after 2,835 lbs (1,286 kg) of heroin was seized from a vessel in the Northern Indian Ocean.

These recent interdictions by warships operating under the CMF umbrella have one thing in common—the ‘stateless’ dhows intercepted across the Northern Arabian sea have an undeniable link to Pakistan. Indeed, in the Indian Ocean, such supposedly stateless dhows with drug cargoes comprise the marine transportation component of the well-oiled, state supported narcotics trade, run by Taliban-linked drug lords in cohort with Pakistani cartels. During boarding operations by law enforcement agencies on the high seas, the crew of such vessels (mostly small dhows) has been found to be mostly Pakistani and occasionally of Iranian origin, with their identification deliberately obfuscated by absence of proper identity documents. The adventurous voyages of drug smugglers to far flung destinations commonly originate from small coves and non-descript harbours dotting the long Makran coast, which forms a rim across Pakistan and Iran. Possibly by design and prior briefing by their mentors and handlers, the vessels avoid flying the flag of any nation on the high seas, fudging their identity and complicating the situation for law enforcement agencies. This ‘grey zone’ in international maritime law has been exploited by Pakistan’s Deep State with ingenuity for many decades to run a gargantuan enterprise based on the unholy nexus of narcotics and terrorism. Ironically, Pakistan too is part of the U.S.-organised CMF, headquartered in Bahrain. Over the past two decades, senior Pakistani naval officers have successfully sought rotational leadership roles in CMF naval task forces to gain legitimacy and prestige.

It is no surprise that with the early U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, the narco-economy thriving in the Afghanistan-Pakistan region has witnessed a marked spurt in smuggling activity at sea over the past year. The deleterious effects of the pandemic on Pakistan’s economy and its adverse impact on budgets available to security and intelligence agencies may have contributed to Pakistan’s renewed boost to smuggle narcotics over the established maritime routes in the Indian Ocean. It is well known that Pakistan’s intelligence agency Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) midwifed the Afghanistan-based heroin trade during the long years of Taliban rule, in the bargain reaping huge profits to fund subversive activities in India. Buoyed by the success of this approach over the years, Pakistan’s Deep State has sought to use land routes to push narco-terror along its international border and Line of Control with India. However, a prominent axis of this drug push into India runs across the sea. In early 2021, the Indian Navy and Coast Guard intercepted suspicious fishing vessels and recovered significant hauls of narcotics off India’s west coast, on two occasions. On April 15, 2021, eight Pakistani nationals were apprehended from a boat “Nuh” off Jakhau coast in Kutch of Gujarat with 30 kilograms of heroin in a joint operation by the Gujarat Anti-Terrorism Squad (ATS) and Indian Coast Guard (ICG). Close on the heels, the Indian Navy recovered more than 300 kilograms of narcotics from a fishing vessel in the Arabian Sea.

In South Asia, no nation is spared the pernicious impact of Pakistan’s enterprise of illicit narcotics export. Island nations such as Sri Lanka and Maldives are major destinations of drug cargos originating from the Makran coast. A recent investigation by India’s Narcotics Control Bureau (NCB) has found that an international drug racket operated by Pakistani drug traffickers jailed in Sri Lanka is increasingly pushing narcotics into India through the sea route using Sri Lankan and Maldivian couriers. The drug network is believed to be spread across Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iran, Sri Lanka, Maldives, Australia and India.

The actual network is much bigger, wider and stronger, as credible reports the by United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) and detailed research by scholars associated with Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime (GI TOC) show. In 2015, the UNODC published an exhaustive report titled “Afghan Opiate Trafficking through the Southern Route”, which remains an authoritative reference on Pakistan’s key role in facilitating production, transportation and marketing of narcotics products originating in Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan. A subsequent research funded by the European Union, published in 2018 as a paper titled “The heroin coast—A political economy along the eastern African seaboard”, conclusively nails Pakistan as the key protagonist in establishing an exhaustive supply chain of narcotics on the east coast of Africa. Experts on trafficking-related issues flag the serious socio-economic ramifications in the region over the past few years, particularly in Kenya, Tanzania and Mozambique, where unflagged dhows coming from Makran coast land their drug cargoes with relative ease. Alistair Nelson, a senior analyst at the Global Initiative against Transnational Organized Crime, estimates that the annual heroin trade by the sea routes in the Indian Ocean originating from the Af-Pak region is worth about US $600-800 million, of which about $100 million worth trade finds its way to Mozambique, for onward transportation to South Africa and beyond, to various destinations in Europe and USA. The arrest and extradition from Mozambique to the U.S., of Tanveer Ahmed Allah, a Pakistani expatriate accused of being a drug lord by American judicial authorities, in 2020, is emblematic of the deep reach of Pakistani drug cartels in southern Africa.

Pakistan’s ‘drug habit’ has long been called out by credible and concerned voices but it seems to have hardly made a dent on Islamabad’s resolve to retain its hold over the illicit economy of intoxicants which keeps its illegitimate coffers on an opiate-engendered high. Incidents of shaming of its national carrier have failed to make any impact. In May 2017, Britain’s Border Force impounded a Pakistan International Airlines (PIA) flight from Islamabad at London’s Heathrow airport after heroin was found hidden in different panels of the aircraft. In March 2018, two members of the cabin crew of a PIA flight from Islamabad to Paris (PK-749) were caught with unauthorised narcotics.

Factors like the wretched state of its national economy, easy availability of poor fishermen in coastal areas as gullible couriers, long established supply chains between Afghanistan and the Makran coast and a well entrenched network of expatriates and other collaborators overseas make narcotics trafficking a highly attractive enterprise for the Pakistani establishment. International opinion has increasingly veered towards holding Islamabad to account for its complicity but Pakistan’s self-styled arbitrators could not care less about consequences of the drug trafficking they ensnare the world with.