NEW DELHI: Chinese President Xi Jinping’s visit to Myanmar last week has left more questions than answers. StratNews Global learns that only two agreements were signed and these were about shoring up the existing agreement on Kyuakhphyu deep-sea port in Rakhine state and the feasibility study of a railway line from Yunnan to Mandalay (feasibility because of terrain and the risks involved in building a railway through insurgent infested forests). It’s not clear where that leaves media reports about China funding a special economic zone and a spanking new city opposite Yangon.

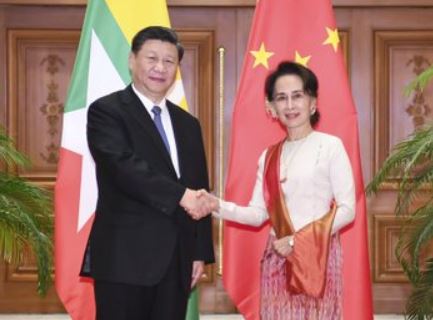

It begs another question: Why would the president of China come all the way for two agreements? It would appear that President Xi was boosting Aung San Suu Kyi’s morale. The Nobel Prize winner and State Counsellor has been on the back foot internationally for defending her army’s conduct in Rakhine state, refuting charges of genocide against the Rohingya in the international court.

This visit also confirms a view that the Chinese president sees Suu Kyi and the army as partners and allies they can do business with. Even if there were limited gains from this visit, it leaves the door open for potentially more business down the road in the form of the China Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC).

CMEC is about all the projects mentioned above and perhaps more that are not yet known. The buzz is President Xi offered to open the purse strings for as many projects as Myanmar wanted (including obviously some of interest to Beijing) but the Myanmarese leadership preferred to go slow.

The sense in India is that with CMEC in the east and CPEC (China Pakistan Economic Corridor) on the west, Beijing is making no secret of its determination to reduce the risks posed to its energy supplies transiting the Malacca Straits chokehold. Opening up new routes to the Indian Ocean is the BRI, which is basically about building infrastructure to serve China’s strategic purposes and is, therefore, a handy instrument. BRI will also help build Beijing’s political influence in the countries where it is implemented, a point which India’s foreign policy brass is cognizant of. They also know India cannot compete with China’s deep pockets and must therefore play to its strengths, which means focusing on smaller projects that cost less, are viable and make a difference to people’s lives.

It is the military impact of what China is attempting which is interesting. A Chinese presence in Kyuakhphyu port in Rakhine state on the Bay of Bengal may at some point lead to Chinese military or naval personnel being stationed there. Don’t forget, China is the main supplier of military hardware and training for the sanctions-hit Myanmar military. India is trying hard to keep up, recently transferring an old Kilo-class submarine to the Myanmar Navy. But there’s only so much India can do given its own capacity constraints. Nevertheless, senior naval officers StratNews Global spoke to said they were not overly concerned about Chinese military presence in the Bay of Bengal. As one of them said, “We can bottle them up given that we have a string of naval establishments all along India’s east coast including Vizag, which is bang in the Bay of Bengal. Add to that the resources we can mobilise from our base in the Andaman Islands.”

The same would apply in the event the Chinese are able to persuade Thailand to approve the building of a canal through the Isthmus of Kra. Any such canal would open into the Andaman Sea, where again India can mobilise the resources of its Andaman Nicobar command. Nor does a Chinese naval presence in Hambantota, Sri Lanka, present any great dilemma for India. In case of hostilities, Chinese ships would be highly vulnerable, given their proximity to the Indian mainland.

The problem, Indian naval officers admit, is Gwadar in Pakistan. Unlike the Bay of Bengal, the Arabian Sea is an open body of water making it difficult to monitor. Gwadar itself is strategically positioned in the northern Arabian Sea, near the mouth of the Strait of Hormuz. India does have a naval deployment in the strait to escort its oil tankers, and has naval facilities in Duqm Port in Oman, directly across from Gwadar. But the Indian Navy may have to contend with the Chinese and Pakistani navies operating jointly.

Indian Navy sources acknowledged capacity constraints. It currently deploys 140 ships with no less than 50 at the end of their service lives. The retirement of these ships is being put off and their operational deployment extended until their replacements arrive (incidentally 48 of these 50 ships are being built in India, two are being built in Russia). Maritime air surveillance using P8I aircraft is also being stepped up.

The Indian Navy is also tying up with other friendly navies with stakes in the Indian Ocean. France is an obvious partner, Indonesia another, so are Thailand, Singapore, Vietnam and Bangladesh. Through joint, bilateral and multilateral exercises, coordinated patrols, disaster relief drills and so on, India is hoping to manage the gap in its deployment with friendly navies pitching in. By 2027 the navy’s deficiency is expected to be filled when it will be able to deploy 175 surface ships, 20 submarines and 500 aircraft (against 230 now).

Until then, India will have to keep up its guard on the CMEC front while ensuring that capacity constraints do not limit its operational capabilities off CPEC waters.

Thirty eight years in journalism, widely travelled, history buff with a preference for Old Monk Rum. Current interest/focus spans China, Technology and Trade. Recent reads: Steven Colls Directorate S and Alexander Frater's Chasing the Monsoon. Netflix/Prime video junkie. Loves animal videos on Facebook. Reluctant tweeter.