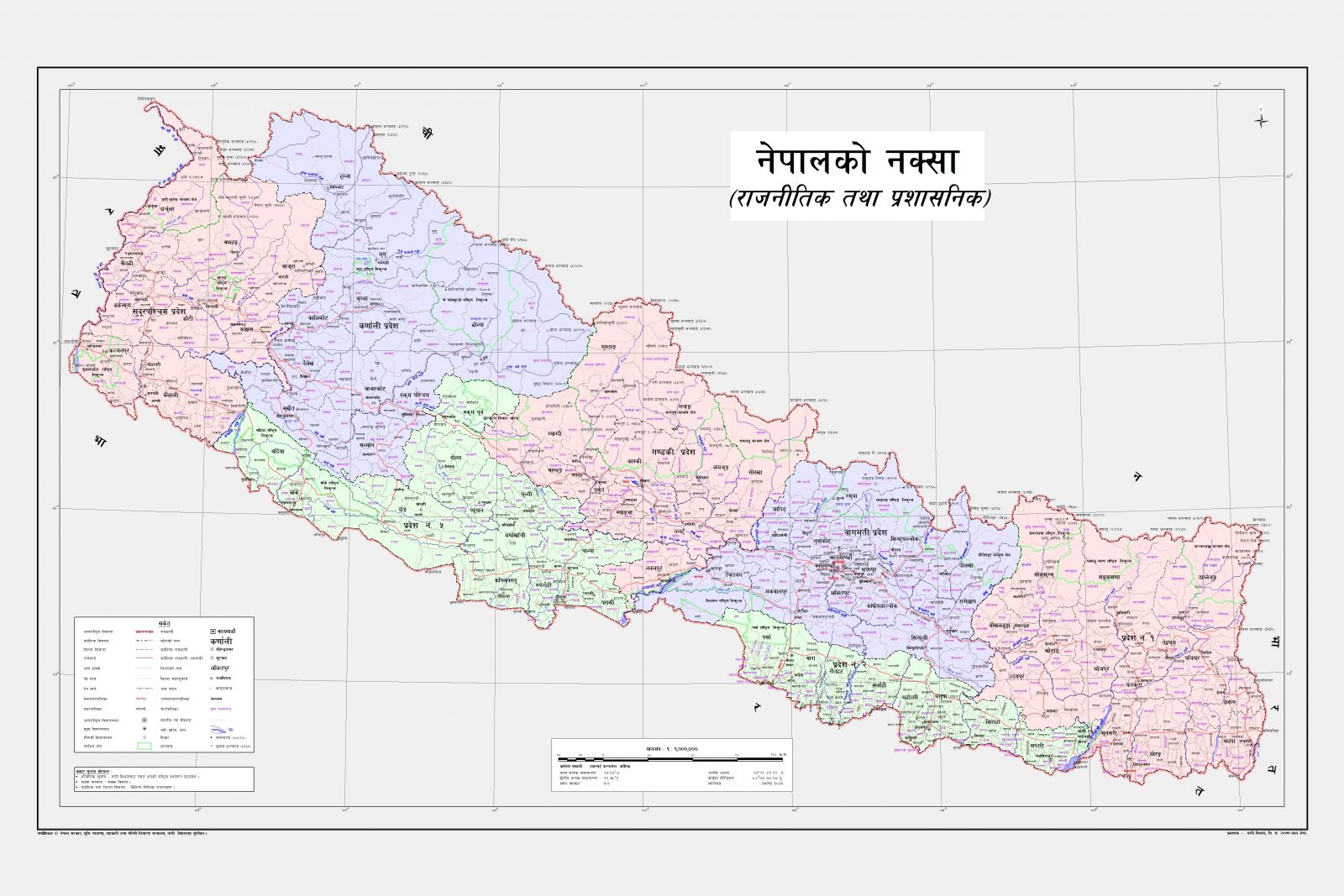

NEW DELHI: An approximately 1,700 km long porous border between India and Nepal has contributed to the deep and strong civilizational and people-to-people links between the two nations. But as often happens with close neighbours, the two are currently at loggerheads over contesting territorial claims. At stake are the territories of Kalapani, Lipu Lek and Limpiyadhura with both New Delhi and Kathmandu claiming them as their own. The strain in ties appeared to boil over last week with a seething Kathmandu coming out with a new political map showing these three territories as part of Nepal. New Delhi responded by saying that such “artificial enlargement of territorial claims” was unacceptable and that Nepal should “refrain from such unjustified cartographic assertion”. Noted Nepali journalist, author and founding editor of Himal Southasian Kanak Mani Dixit tells StratNews Global Deputy Editor Parul Chandra in this e-mail interview, that it’s time for the prime ministers of the two countries to discuss and resolve the dispute. In this interview, Dixit also observed that India will lose ground in Nepal only if it considers itself as a hegemon. As for increasing Chinese inroads in Nepal, Dixit said these reflected China’s larger geopolitical aspirations in his country, in South Asia and globally. At the same time, he warned that China could face a backlash if the Nepali people begin to feel that Beijing’s engagement in the country is transforming into adventurism. Read on for more:

Q: What has triggered Nepal’s decision to come out with a new political map, including in it Kalapani, Lipu Lek and Limpiyadhura? Could it not have waited to resolve the dispute through discussions with India? Or was it a case of Nepal simply losing patience with India after its request to have foreign secretary-level talks on Kalapani, made in November last year, remained unheeded?

A: The main issue concerns the triangle made up of Lipu Lek, Kalapani and Limpiyadhura that Nepal regards as its own under the Sugauli Treaty of 1816, which defines the Mahakali (Kali) River as Nepal’s western border. Some time in the late 1850s, some British maps started showing a small rivulet heading northeast from the main river stem as the Kali. Kalapani is east even to this rivulet. So, Nepal has had two demands–one is to claim Kalapani, where India has a military garrison. The second is the entire triangle up to the Limpiyadhura ridge.

For years, Kathmandu had been in communication with the Indian Foreign Ministry to start foreign-secretary level talks, which was meant to take up the few remaining border disputes between the two countries. However, instead of sitting down for talks, India carried out four consecutive actions which constitute the trigger for the present crisis leading to Nepal publishing its new political map: a) agreement between PM Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping in Xian in May 2015 to use Lipu Lek for trade; b) publication of a new official political map by India in November 2019 which included the disputed territory; c) inauguration on 8 May of the ‘link road’ to Limpiyadhura by Defence Minister Rajnath Singh; d) a statement by the Indian Army Chief implying that the Nepali position was being instigated by China. These were, consecutively, acts of provocation while Nepal had been waiting for New Delhi to sit down to talk.

Q: Was the decision to come out with a new map also a consequence of Nepali Prime Minister K.P.Sharma Oli’s battle for political survival as he faces the prospect of being ousted by his own party men, and the need to live up to his “nationalist” credentials?

A: Yes, Prime Minister KP Oli had kept the matter pending and stopped release of Nepal’s new map which had been prepared back in January itself, while waiting for the Indian foreign ministry to come forward for talks, even as the matter escalated. He waited even as he was weakened within his party as the senior-most members in the CPN ‘secretariat’ –including Maoists as well as his colleagues in the former UML–worked in unison to isolate him. A pre-existing condition for his weakened position was also the poor governance under his prime ministership, added to that a hostile media. As matters came to a head, and with the ‘secretariat’ as well as the opposition parties demanding that he publish the new map, he decided to publish it and go the whole hog. As far as KP Oli’s ‘nationalist’ credentials are concerned, he was after all the main leader who stood up, and with the people at large, against the Indian blockade of 2015-16.

Q: Indian army chief General M.M.Naravane has insinuated that Nepal’s protests on Lipu Lek could have been at China’s behest? This led to outrage in Nepal especially as it’s a country that prides itself on its sovereignty. Your comments.

A: China becoming more engaged in Kathmandu is a fact, and remember that this engagement was accelerated by the Indian blockade which forced Nepal to look north. However, for the Indian army chief to insinuate that Nepal’s protests on Lipu Lek were instigated by China was silly. It showed a lack of understanding of Nepal’s sense of self, which is worrying coming from a neighbouring country’s army chief, and lack of appreciation of the long history and most recent timeline of this dispute. Further, how could Gen. Naravane have been ignorant of the fact that the main trigger to this crisis was actually an agreement between India and China on a territory Nepal considers its own?

Q: China has made tremendous inroads into Nepal, including in its polity and this in turn is causing India anxiety. The Chinese ambassador to Nepal Hou Yanqi, going by reports in Nepali media, played the role of peace-maker among the warring NCP leaders recently. Does China’s growing influence in Nepal as well as the activities of the country’s envoy a cause for concern?

A: Yes, the Chinese ambassador has been much more active than her predecessors, even intemperate, and this probably has to do with China’s larger geopolitical aspirations in Nepal, South Asia and globally. Besides, Nepal did reach out to China as a fallout of the Indian blockade for trade and transit linkages and road openings. On the other hand, the Beijing authorities have to understand that there will come a tipping point as and when Nepali public opinion feels that the Chinese engagement is escalating into adventurism. For now, it seems like China is on a path of making the same mistakes that India did in Kathmandu, and under-estimating the resolve of the Nepali civil society and the public at large.

Q:What in your perception is making India lose ground to Nepal despite the close and historical ties the two countries share?

A: India is losing ground only if it thinks it should somehow control Nepal as a hegemon. Otherwise, you could say that the India-Nepal relationship, unique as it is and marked by an open border and deep cultural and societal ties, is coming to its proper equilibrium for the first time since India attained Independence in 1947, and Nepal entered the modern era in 1950 with the end of the Rana regime.

Q: Are the current tensions headed the same way as in 2015 when India imposed an unofficial blockade? And how can these differences be resolved?

A: That would be up to New Delhi, and I would certainly warn against any such thinking as it is bound to backfire rudely. Nepal certainly would not want to see a replay of the events of 2015, for that would bring more hardship on a people who are trying to rebuild after the 2015 earthquake and the blockade of 2015-16, and who are presently grappling with the Covid-19 pandemic.

It is urgent for Mr Modi and Mr Oli to get on the phone and to work double-time for de-escalation and delinking. De-escalation can start with stopping all work on the Lipu Lek ‘link road’ and allowing negotiations to begin through an open-minded study of archives and agreements. De-linking means isolating the Limpiyadhura controversy from all other aspects–economic, cultural, societal–of the Nepal-India relationship. For now, Kathmandu and New Delhi can start by agreeing to disagree on the Limpiyadhura triangle.

Professional newshound, have navigated through typewriters, computers and mobile phones during my over three-decade-long career working in some of India's finest newsrooms (The Times of India, Financial Express). Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh and Bhutan are my focus, also Sri Lanka (when boss permits). Age and arthritis (that's a joke) have not dimmed the thrill of chasing a story. Loves music, animals and pasta.