Veteran author and journalist Bertil Lintner has been reporting on Myanmar for decades. In this wide-ranging interview he talks to The Irrawaddy editor-in-chief Aung Zaw about China’s goals and strategy in Myanmar—including its relations with the National League for Democracy and the ethnic armed groups—the future of Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the most likely scenarios for ending the military’s grip on the country.

Aung Zaw: Thank you Bertil. I think we will have a long discussion. We’ve covered the peace process and ethnic states, the ethnic army EAOs [ethnic armed organizations]. Now I want you to talk about China, Burma’s powerful neighbour. I want to hear your thoughts on China’s political clout and geopolitical ambitions, because we often debate and talk about China’s roles in Myanmar’s internal affairs and internal conflicts; how China interferes in Myanmar’s domestic affairs and also China’s geopolitical ambitions and access to the Indian Ocean.

Bertil Lintner: Well, first of all, if you look at the map of China, it’s a huge inland empire with a comparatively short coastline for such a big country. And then China decided to change its economic system from socialism to capitalism—their development model was exports. The export industry was developed in order to give the country income and so on, and lift the living standard. And the coastal provinces took off immediately because, naturally, the ports were there. And that’s where the production was taking place. This was Guangdong, Fujian and later Shanghai. Whereas the landlocked inland provinces were lagging behind. And the difference in income between the coastal provinces and the landlocked inland provinces was becoming so severe that it could actually threaten the entire unity of the country. Because China is actually massive, it’s a continent… it’s more than a country. It’s huge. And you have many different ethnic groups there as well. So back in the 1980s, the Chinese started to look at the possibilities for development, export-oriented development in the landlocked inland provinces. And this was published in the official Beijing Review in 1985, the official magazine.

AZ: Yes, I have read that one.

BL: Well, they mentioned that the three provinces were Sichuan, Yunnan and Guangzhou—with a combined population of 100 million people. There is no way they could develop an industry there and send goods to China’s own ports. They had to find an outlet through another country. If you look at the whole of China, the same thing applies. And there are only three countries which border China that have direct access to the Indian Ocean, bypassing the Straits of Malacca and the South China Sea and making it easier than promoting exports to China’s own ports. That’s Burma, India and Pakistan. India, forget about it. There is no way they’re going to help the Chinese…

AZ: No.

BL: Pakistan, yes. There is a highway there, the Karakoram Highway. But it’s one of the most dangerous highways in the world. And then of course, you have all the political turmoil of Pakistan, which is, you know, can be quite frightening. So you see, there is actually only one country that provides easy and convenient access to the Indian Ocean for China and that is…

AZ: Burma.

BL: Yes. So, therefore, China has long-term strategic interests in Burma, which other countries don’t have. The West can talk about human rights and democracy and this sort of thing, which is of course good but it wouldn’t have any real impact on what’s happening in the country. And India is of course worried about Chinese influence; so far they haven’t been very successful in countering it. Whereas China has gone full speed ahead in developing relations with the country. Actually, regardless of who is in power, even when Aung San Suu Kyi was becoming State Counselor, the Chinese Embassy was the first to congratulate her on her election victory at that time. And it was sort of…

AZ: And she was invited to China even before the election in 2015, and she met with President Xi Jinping.

BL: Absolutely. I think the Chinese would prefer to have a “stable” military government in power.

AZ: But weak.

BL: Yeah, but not too strong.

AZ: Not democratic.

BL: No, they wouldn’t like that. But even when Aung San Suu Kyi was… not running the country—it was still being run by the military, we have to remember that, but she was at least running the government—the Chinese made an effort to establish very close and cordial relations with her and the NLD as well. So, my only point is that if you look at China’s long-term strategic interest, they would prefer a government which they can deal with more easily, a non-democratic government; but if it’s a democratic government, they will deal with that too, in their own way of course. And China’s relations with the various EAOs follow the same kind of…

AZ: Yes, that’s my next question. You know in the past communist China exported revolution to neighbouring countries including Burma. But today China wants to export goods and wants to trade with neighbouring countries, and we are part of the Belt and Road Initiative—gigantic projects. We have the China Myanmar Economic Corridor [CMEC] … China and Burma have signed an agreement to implement so many mega projects. Some of the projects have started in Shan State. There have been feasibility studies done as far as we understand and there are so many EAOs and militia active in Shan State. A lot of CMEC projects will start from Shan State and in these areas with EAOs like the Wa, Kokang, TNLA [Ta’ang National Liberation Army] and even the Arakan Army [AA]. China has been providing arms to support those groups; this northern part seems to be part of [a Chinese enclave]. So in the last five years or six years we also saw China aggressively involved in the Myanmar peace process, can you tell us more on this subject and also I want to ask you a quick question: Can China be trusted?

BL: Well, this question is very easy to answer. No. Trust in the sense that they are interested in the genuine peace of the country. They are not. Because it’s not in their interests. If you look at the United Wa State Army, and Kokang as well… They are basically successors to the CPB, the Communist Party of Burma. They received massive support from China from the late ’60s, ’70s to until the 1980s. At that time, China was exporting revolution. Now they’re exporting consumer goods. But it would be foolish of the Chinese to give up the foothold they had inside the country to the CPB because of the 1989 mutiny. They probably have even better relations with some of the Wa leaders than they ever had with the CPB. Because they speak the same language, to begin with. And most of the Wa leaders speak Chinese as a second language, whereas very few of the CPB leaders ever did that. And if you look at the arms that the Wa have, they’re more sophisticated, they’re more heavily armed than the CPB ever was. And all of those guns are all coming from China. Period. There’s no discussion about that. Doesn’t matter how much China’s think tankers deny that. But then if you look at the broader picture; let’s say for argument’s sake that tomorrow all the ethnic groups sit down and they agree that, ‘Yes, we want to have a federation or a confederation that looks like this, sign an agreement, there is no more fighting in the country, there is peace, and all the armed groups will become local police forces or something else.’ Who would be the first to lose? China. It’s not in their interest to see that. China wants to have a certain degree… they don’t like total chaos because it would mean refugees coming into Yunnan and so on. But they are not interested in [total] stability either because they can’t control anything. And they want to have a certain degree of stability, over which they exercise some degree of control. And that is actually the situation now.

AZ: They want to keep the forces against each other.

BL: Yes, definitely. It’s not in their interest to see them give up the struggle. Not now. Maybe someday, in the future, you don’t know but certainly it’s not in their interest today. China is not interested in peace, it is interested in a kind of situation that makes the country… it shouldn’t be too stable because they can’t control it. And they have connections with everybody. But China has a very peculiar foreign policy. They differentiate between government-to-government relations and party-to-party relations, and it’s quite ridiculous for the country where there is only one political party and that party controls the government in China. So, they have government-to-government relations with whoever is in power—in Yangon, previously, but now in Naypyitaw. But party-to-party relations—they can have that with anyone. So they have party-to-party relations with the Wa, the Kachin, with the NLD [National League for Democracy], with the USDP [Union Solidarity and Development Party], everyone. And they would say, ‘Oh this is different. This is party-to-party; not government-to-government.’ But of course, it’s all part of the government strategy mapped out by the party, which controls the government.

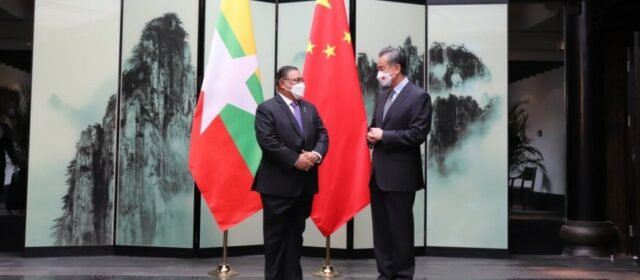

AZ: This year in April, the Chinese Foreign Ministry invited the Myanmar foreign minister, Burmese foreign minister, Wunna Maung Lwin, to China. Foreign Minister Wang Yi said, “No matter how the situation changes, China will support Myanmar in safeguarding its sovereignty, independence, and territorial integrity; in exploring a development path suited to its national conditions.” But we were discussing, … how China was trying to control the forces inside the country, we talk about China’s enclavement and now China was promising the Burmese that they will respect their territorial integrity.

BL: But they’ve never done that. First, it supported the CPB for 20 years. And they had relations with certain EAOs on the border. They’ve always been a player in domestic politics in Burma, especially when it comes to the various armed groups and organizations there.

AZ: Then, what will happen to Burma, or Shan State in particular, where a lot of huge projects are coming in the next 10-20 years, whether we like it or not? This is quite worrying, that the Chinese are coming, and even the Wa, known to be a proxy of China, are moving to the southern part of Shan State. Thailand is also looking at it with worry.

BL: Well, I don’t think China wants to annex certain parts of the country. That is not the way they exercise influence and how they expand their spheres of influence. Actually, what China is doing in Burma today, the plan, predates the Belt and Road Initiative. In the ’80s, they were looking at the waterways, railways, roadways, through Burma, from Yunnan down to the Indian Ocean. They were talking about how it should be developed. And of course, that is interference. It’s not just help. They are not doing this out of the goodness of their heart. They have economic, political and strategic interest in controlling the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor as it is called today. And they are going to continue doing that. If you look at EAOs that.. but you always have to remember that even though they are very dependent on China—because they cannot exist without what they are getting from across the border—it doesn’t mean that they are necessarily pro-Chinese or pro-China, let’s put it that way. The Kachin, we know they are not. I mean, they are Christians and … they are not trusted by the Chinese either, that’s why the Chinese are not giving them any weapons; and they are getting them from other sources. Even the Wa, they are not happy about the Chinese dominance. They are fiercely independent people. And they know how the Chinese central authorities treated the Wa in China in the 1950s. They haven’t forgotten that.

AZ: China is not trusted—I got it. But today, the Chinese government seems to be backing and supporting the military regime in Burma, which the Burmese people hate and despise; the Burmese people loathe it. Last year we saw anti-China demonstrations taking place in Yangon and other cities. Chinese factories were attacked. Later, this year and last year we have seen local armed groups, opposition groups, make a threat against Chinese companies and a gas pipeline and copper mines inside the country. China is also trying to reach out to some opposition members as well as to the NUG [National Unity Government] government in exile asking them to protect Chinese interests and Chinese businesses in the country. And the Chinese have also asked the regime to protect [their interests] at all costs, to prevent any attacks on Chinese interests and Chinese business in Burma.

BL: Well, it sort of underlines the whole thing that … the way the Chinese are reacting to this, that they even started talking to the National Unity Government and all the armed groups and this sort of thing—on a “party-to-party” basis though. But their long-term strategic interest remains the same. And there is a corridor, an outlet to the sea, the outlet to the Indian Ocean. And therefore, they have to play, they cannot afford to antagonize certain groups because that will backfire. Back in the SLORC days, they actually put all the eggs in one basket, they supported only the military. And they had no link to the opposition at all, of course to some of the EAOs but they were sort of different. But even there, they showed a certain degree of flexibility—that they didn’t really want to antagonize, not even the NLD during its early days of its existence. And I can tell you an anecdote that reflects that, in a curious kind of way, a peculiar kind of way. After the 1988 uprising, everyone was at Aung San Suu Kyi’s compound at University Avenue. All the activists, the doctors, the lawyers, the politicians, the journalists—everybody. And the Western embassies went there to meet her and the NLD leaders. The Chinese diplomats did not. But one day, I can tell you the story now because it was Michael Aris, who was Aung San Suu Kyi’s late husband who told me. He’s gone now and I don’t think he would mind my telling this story. And he was there of course in the house in University Avenue. The Chinese diplomats never came to talk to Suu Kyi. But one day, they saw a car, a diplomatic number plate, the Chinese Embassy coming into University Avenue. And everyone was surprised. And then the junior officer from the embassy came with a big box full of books in Tibetan about Tibetan Buddhism. It was their way of indirectly saying that “We are careful but we are not, well, don’t look at us like we are some kind of enemy. It was not to Suu Kyi, it was to her husband. It’s about Tibetan Buddhism. But that gesture showed that everyone, I think, even at that time, the Chinese wanted to maintain a certain degree of flexibility. They didn’t even know if the military government was going to survive or not. What the future would look like. Because, again, their long-term interests remain the same. And they are playing various games accordingly. And that’s what happens.

AZ: But in the last 30 years, since SLORC-SPDC came into power, we have seen massive exploitation of natural resources by the Chinese in the northern part of Myanmar.

BL: Yes. In Wa State it is tin and rare earth metals. When we’re talking about Chinese exports of rare earth metals, it’s only half the truth. Most of it actually comes from the Wa Hills. The Chinese… also have two rare earth mines up in Kachin State. Of course to export these kinds of items makes it possible for these armed groups, like the KIO, the KIA and UWSA [Kachin Independence Organization, Kachin Independence Army and United Wa State Army] to maintain their organizations, to get more arms and run … whatever they have inside their respective areas. But so, they are dependent on each other in a way. But I would argue that if there was a central government in Myanmar with a more enlightened approach to people like the Wa, the problem could be solved. I think they would be happier staying with Myanmar than to be, you know, totally dependent on China. But so far, it is so easy to dismiss them as drug traffickers and, you know, whatnot. They are, I mean they used to trade in drugs. There is no doubt about that. But today, their sources of income have become more diversified and even if they get money from drugs, who hasn’t done that in Burma—including the government?

AZ: Last year, a Chinese special envoy visited Burma twice after the coup. He reportedly asked coup leader General Min Aung Hlaing to allow him to meet with the detained State Counselor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi. And he was denied [permission]. And again, we heard the news that the Chinese told the Burmese not to disband the National League for Democracy. Do you think China has political leverage over Burma, compared to other Western countries or Western governments?

BL: Well, you’ll also have to remember that as you mentioned before, the Burmese military is fairly xenophobic. They haven’t forgotten the long and bitter war with the CPB. A lot of soldiers were killed, their boys were killed, with Chinese guns. And a retired officer once told me it’s like a scar in the heart. They cannot forget that. And then of course, you know, in the beginning, after the coup in ’88, they had to rebuild, or strengthen their armed forces. At that time, it was only China that was willing to sell them anything. But they became so dependent on China, so they had to look for alternatives. They didn’t want to have this heavy dependence on China. So they turned towards… Russia. Of course, it worked for a while, but it’s not going to work much longer, given what’s happening in Ukraine right now. So, they’re back in the Chinese camp, very reluctantly, and I don’t know how they would want to handle that. And they are not particularly happy about it either. And the Chinese of course, they know this. They know that the military doesn’t like them, they don’t trust them. But I think actually they find it easier to deal with Aung San Suu Kyi than Min Aung Hlaing, in a way—a very strange and peculiar way. So, there were even some reports before the 2015 elections that the Chinese wanted to see the NLD win rather than the USDP. Maybe because it would give the country a bit more, a degree of stability at that time. And instead of military rule, which would be resented by everyone. But the Chinese are playing all these different games at the same time, and it is very important to look at the bigger picture and see a pattern and see where it leads to. They don’t just sign with one particular actor or one particular group. And therefore, the Chinese policy towards Myanmar or Burma is very different from that of Western countries, which are more sort of ideologically motivated.

AZ: Definitely, Burmese people, including the military, are Sinophobic. Burmese people in general are pro-Western, they are not pro-China. You know over the past decades we have seen the US politically invested in Burma promoting democracy, human rights and press freedom in Burma or Myanmar. Recently the US invited the foreign minister of the NUG to Washington DC while the US-ASEAN summit was taking place. Definitely, there was competition between the US and China. I think there is competition, rivalries between the US and China. And this Cold War mentality is coming into the Indo-Pacific region including ASEAN. Burma is also one of the countries where the US and China are trying to gain influence. What are your thoughts?

BL: Well, if the United States wants to get more influence in the country, they will also have to be more active than they are today.

AZ: Like in Ukraine?

BL: Well, maybe not to send all the weapons that they’ve been sending to Ukraine; maybe there is another way of doing it. But certainly, it seems to be that Burma is now on the backburner when it comes to American foreign policy. They are much more… entirely preoccupied with Ukraine, what’s happening in Europe. And therefore of course, the road is wide open for the Chinese to…

AZ: What I remember was, in 2007-08, US policy was very consistent, engaging with Burma stakeholders and all sides, all forces. It was very active, and I would say that it was quite impressive.

BL: If you look at America’s or Washington’s Burma policy, that was engaging everyone … It predates the 2015 election victory for the NLD. Even during Thein Sein, he was invited to the White House, and I think the Chinese, at that time, felt—and I have seen translations of articles in Chinese academic journals saying—that ‘We have lost Burma to the West’. That’s the way the Chinese felt. And therefore, they had to reestablish their influence in Burma. And they did so very cleverly really. They started talking to more so-called ‘stakeholders’—a term I really don’t like—in the country; not just the government. They started engaging the media, for instance. They’ve never done that before. They invited journalists to China, started talking to journalists. The ambassador in Yangon suddenly answered the phone when journalists rang him and they went to talk to all the different political parties. Just to, in a way, to counter the spread of American influence. Economically of course, they were always much stronger than the United States when it comes to investments and so on. But when it comes to sort of people-to-people relations, they were way behind the Americans at that time. And they tried to reestablish some kind of—not reestablish because they never had any—but to establish some kind of better relationship with the public, the general public in Burma. If they succeeded or not? I’m not sure. I don’t really think so. But at least they tried; they realized that it was important. They couldn’t just “lose” Burma to the West, as some of their academics said at that time.

AZ: I am curious. Do you think Aung San Suu Kyi still has a role in the future? She is now 77.

BL: No, I mean she’s done her thing, and she’s meant a lot to the people of Burma. The role she has played cannot be denied by anybody. But she’s old and she’s tired. And many young people have even become critical about her because they think she could have handled things in a different way.

AZ: The mis-steps.

BL: Yes, exactly. So, I think we’ll have to wait for the next generation. And the next generation—I mean, among the Burmans as well as among the other groups. Many of the ethnic leaders are also stuck in the past. Old visions, old ideas, they do not know how to move forward.

AZ: And my last question. Any democratic transition would stall in any country unless the powerful armed forces are brought under civilian control in the context of a balance between executive power and legislative branches of government. Democracy can exist only where the soldiers are the servants, not the masters, of the state. The military in Burma is different, the Burmese army is unlikely to assume the servant role, so until it does, the prognosis for Burmese democracy cannot be good. Because the Myanmar military is going to stay in power indefinitely.

BL: That’s what they want to do, yes. But you have to remember also when the military first seized power in 1962. It was at a time when there were military coups all over the world, in the so-called Third World. I mean Thailand had coups, a couple years later there was turmoil in Indonesia, Africa, Latin America and so on. But in most countries, the military were content with seizing political power and they left economic power, running the economy, to other interests. Take Thailand for instance, there was a marriage of convenience between the military and the Sino-Thai plutocracy. And they let them run the business, and that’s why Thailand’s entirely prosperous today. Indonesia had a very similar kind of arrangement, and other countries too. But the 1962 coup in Burma was different because the military seized political as well as economic power. And that economic power was what they called the ‘Burmese Way to Socialism’. In which everything was nationalized and placed under military-controlled—they would say state-controlled but it was mainly military-controlled—state corporations. […] Even when they started introducing new economic reforms after 1988, they’re dependent… the military is still a strong player. And the so-called cronies are entirely dependent on military support. And the relationships between the cronies and the military are not the same as between the rich Thai entrepreneurs and the government, with the military here [in Thailand]. Here they kind of let each other run their own thing. And then everyone benefits from it.

Now the military is going after some of the cronies too. But how can you do that if you want to see the country develop? So, the power structure in Burma is so different from any other country I’m aware of really. You have a military which [holds] economic and political power – and wants to control everything. But if you can break that. Well, I don’t know how it is going to work … to be frank. But it can only happen from within the military. And the problem there is of course that if there is a serious split in the military, not just some defections, you may have to see a very bloody civil war.

AZ: Always great to talk to you, Bertil. Thank you so much.

(By arrangement with ‘The Irrawaddy’)