NEW DELHI: Since the beginning of May this year, China has created an arc of sustained military pressure along India’s northern borders. This presently stretches from Daulet Beg Oldi in Ladakh, to Naku La over a thousand kilometres to the East in north Sikkim and possibly on to Bhutan. China’s action appears to blend military, civil and diplomatic instruments.

Confrontations between Indian and Chinese troops, or Chinese military activity, have been reported from a number of places including around Daulet Beg Oldi, Gogra, Galwan Valley, Chushul, Pangong, Demchok, Shiquanhe, Rudok and Naku La in north Sikkim. Such a military build-up takes planning and preparation. At least three military sub-districts (MSD), namely Hetien, Ngari and Shigatse, subordinate to the Xinjiang and Tibet military regions, are involved in this military build-up. Both military regions come under the PLA Western Theatre Command (WTC), which exercises operational jurisdiction over the Chinese side of the entire 4,057-km border with India.

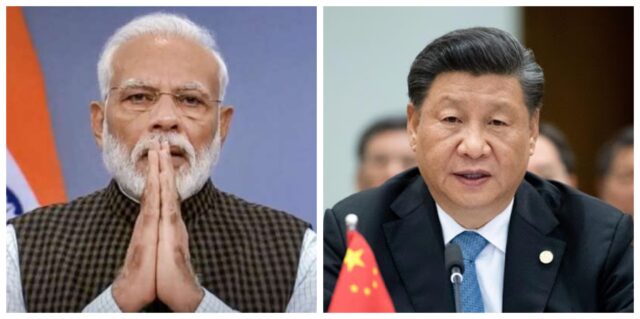

Among the WTC’s tasks is safeguarding Chinese nationals and assets at the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Such an operation involving multiple MSDs, as also induction of additional troops, heavy equipment, tanks, vehicles, artillery, aircraft etc to reinforce the WTC and MSDs will have required careful planning and coordination, including between the WTC and the Central Military Commission (CMC) chaired by Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing. It would certainly have been approved, if not initiated, by Xi Jinping who is also Chairman of the Central Military Commission and Commander-in-Chief of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

There is also potential for additional tension on the Tibet-Bhutan border opposite Drowa village in Lhodrak County, Shannan, Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), where a report indicates the PLA is constructing or upgrading a Military Training Base (Base No. 32) since May 8. Four fighter jets and 21 military buses were reported to have been sent from Gongga Airport to the construction site of Base No. 32 on May 14. Another 100 army buses are expected to reach the site this month. Coincidentally, Men Chu Ma village, which is a disputed area between China and Bhutan and has been developed as one of China’s ‘model well-off border defence villages’, is also in Lhakang Township, Lhodrak County, Shannan, TAR, or Bhutan’s Kurtoe Lhuntse District.

Additionally, related civilian activity by the TAR and Rudok County administrations pointing to long term interest in the Pangong Lake has been noticed. On April 21, Dorjee Tsedup, Deputy Chairman of the TAR People’s Government and Head of Pangong Lake Governance, travelled to Ngari (Ali)’s Rutok County to inspect the Pangong lake and its environment. He was accompanied by the Deputy Commissioner of the Ngari Municipal Administrative Office and other senior officials of Rutok and the Pangong Lake district. Interestingly, Dorjee Tsedup’s instructions hinted at long-term plans for Pangong Lake. He told assembled officials that “Pangong Lake, being an international lake, must receive special care and attention for maintenance and improvement of the lake’s ecological environment.” He emphasised that law enforcement and protection of the lake “is important for long-term work”. Days later Rutok County’s Judicial Bureau and the Ngari Regional Customs and Commerce Bureau officials conducted propaganda campaigns in the border villages of Deru and Jaggang also known as Chagkang village, not far from Demchok in Ladakh, India. They explained the alignment of China’s border. In late May, the Ngari Municipal Public Security Bureau revealed that all Public Security personnel in Ngari had received “three-stage intensive real combat training”.

Simultaneous with this activity, Beijing has seemingly encouraged Nepalese Prime Minister KP Oli to open another front of pressure on India. Oli owes his continuance as Prime Minister to the efforts of China’s Ambassador to Nepal Hou Yanqi and Xi Jinping’s 40-minute telephone conversation with Nepal’s President. China’s action has the potential to be a long-term problem for India.

A number of factors have contributed to China’s actions. In addition to the steady slide in bilateral relations over the years, is Chinese President Xi Jinping’s bold operationalisation of the geo-strategic ‘One Belt, One Road’ in the region with the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) in April 2015. Since then Chinese leaders have been telling India at every interaction, whether at the official level, Track 1.5 or Track 2 meetings, interactions with think-tanks etc., that India ‘must resume talks with Pakistan to ease tensions, resolve the Kashmir issue and then look to improved relations with China!’

Beijing maintains this pressure on India with the aim of safeguarding its huge strategic and financial stakes invested in the larger Ladakh area, including Aksai Chin, Gilgit, Baltistan and Pakistan occupied Kashmir (PoK). The Indian Army’s surgical strikes in PoK and subsequent air strike on the Jaish-e-Mohamed (JeM) terrorist training camp at Balakot in Pakistan together with the rapid improvement of defence logistics infrastructure on the Indian side and revocation of Article 370 have raised China’s apprehensions. China has consequently raised the Kashmir issue in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) on four occasions thus far in coordination with Pakistan. China’s large stakes in the region leave open the possibility of Beijing resorting to a military option.

There is also serious domestic pressure on Chinese President Xi Jinping. The growing discontent caused by various factors like the abolition of term limits on appointments of cadres to senior posts criticised by cadres as a return to the ‘one-man rule’ of Mao, rising popular dissatisfaction because of increasingly restrictive and stringent security policies and expanding intrusive Party surveillance have provoked wide criticism. The economic downturn, accentuated by the US-China trade war and burgeoning unemployment, estimated this March at between 70-80 million, has broadened the pool of popular dissatisfaction. The initial mishandling of the outbreak of the Coronavirus pandemic at its epicentre in Wuhan sparked a widespread surge of anger. Almost unprecedented for China was that popular criticism was directed at the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and Xi Jinping personally.

At the same time, the developments in Hong Kong, Taiwan and the adverse impact of the U.S.-China trade war on China’s already slowing economy, gave rise to the popular perception that Xi Jinping’s assertive foreign policy was not working and the ‘Two Centenary’ goals (‘China Dream’ by 2021—the hundredth year of the founding of the CCP—and making China a ‘major power with pioneering global influence’ by 2049, the centenary of the founding of People’s Republic of China) was slipping from the leadership’s grasp. A think-tank of China’s Ministry of State Security recently cautioned that global anti-China sentiment was growing exponentially and could even lead to conflict. The PLA Daily (May 5) warned that the socio-economic situation was “bleak” and at a “high explosive situation” and foreign powers could accelerate a recession and create social upheaval. Since February Xi Jinping adopted a series of tough measures to retrieve his and the CCP’s credibility. These include pressure on Hong Kong, Taiwan and now, India. There have also been regular critical references to India in China’s military media over the past year and, most recently, at the National People’s Congress session that concluded on May 28.

Viewed in this backdrop, the activity at multiple points along India’s borders is different from earlier intrusions and certainly tests our military preparedness and political responses. It suggests a larger objective—reflected again on this occasion with reiteration of China’s claims on the whole of Ladakh and Galwan Valley—either immediate or in the near future. It also raises the question as to whether Xi Jinping can yet again risk denting his credibility by withdrawing his forces without showing some gains.

(The author is a former Additional Secretary, Cabinet Secretariat, Government of India, and is presently President of Centre for China Analysis and Strategy. Views expressed in this article are personal.)