Last year, the city of Handan in northern China began to reverse an exercise it had started four years earlier: changing the names of 33 streets from idioms to something more prosaic and easily understood by ordinary people. The irony is Handan has more than 1,500 idioms associated with the city, many going back in time. The moral of the story is that even Chinese can have issues with idioms.

Idioms figure not only on streets but have historically been used in a political context, for instance to discredit or attack rivals. Deng Xiaoping, who led China from 1978 to 1992, was purged twice for saying “It doesn’t matter if a cat is black or yellow as long as it catches mice”. Meaning, “if economic reform helped China develop, it wasn’t a bad thing.”

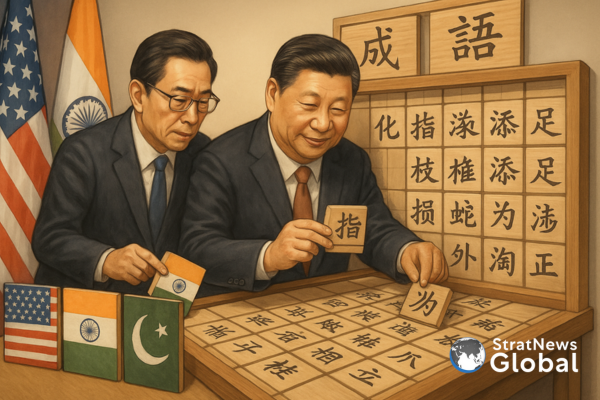

Idioms or chengyu comprise four characters, and are drawn from old stories, historical events, or ancient philosophy. They express complex ideas with cultural and moral lessons. For example, to draw legs on a snake warns against doing unnecessary things, while calling a deer a horse is about twisting facts to mislead others.

These idioms have existed for over 2000 years, originating in Confucian classics like The Analects and Mencius, historical chronicles such as The Records of the Grand Historian, military strategy texts like Sun Tzu’s Art of War, and folk tales passed down through generations.

In the past, emperors, generals, and scholars used idioms to teach, warn, or advise others, embedding moral lessons within diplomatic and military discussions. Even today, these idioms remain a powerful part of Chinese communication, often carrying layered meanings in official statements and media narratives.

Idioms also serve as coded communication in official speeches and state media, signalling positions without direct confrontation.

INDIA

During the 2017 Doklam standoff, China Daily used this idiom in its headline, “He (India) who tied the bell on the tiger’s neck must untie it”, basically accusing India of fanning the Doklam tensions and must withdraw its forces to resolve the crisis.

Another idiom used by China is “Kill the chicken to scare the monkey”, meaning a street performer controlled his monkey by killing a chicken in front of it, showing what would happen if the monkey disobeyed. China uses this to pressure or blackmail smaller South Asian nations (Nepal, Maldives, Sri Lanka) to align with Beijing’s interests, indirectly signalling to India not to challenge China’s expanding regional footprint.

RUSSIA

The idiom “When the lips are gone, the teeth feel cold”, describes the close strategic relationship with Russia. This phrase shows interdependence—if one is harmed, the other will suffer too. When used in official commentary, it underscores shared security interests: if one falls, the stability of the other is at risk.

Last month, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi told an EU diplomat that “China does not want Russia to lose” in Ukraine. He was warning that a Russian defeat could shift US focus towards China.

PAKISTAN

For Pakistan, China uses the idiom “Iron brothers”, meaning an unbreakable, deeply trusted relationship, showing unwavering support across political and military areas.

BANGLADESH

For Bangladesh, China uses idioms like “crossing the river in the same boat”, meaning working together through difficulties, and “true friendship is seen in adversity”, meaning real friends prove themselves during hard times. These idioms project China as a reliable partner during crises, strengthening Beijing’s soft power.

Additionally, China often uses “peaceful development”, seeking to reassure partners that China wants to build ties based on mutual benefit.

Recently, with reference to SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation), China said it would “set up a new stove elsewhere”. In other words, China and Pakistan were working on a new regional group to replace SAARC, which they said had failed under India’s leadership.

China was telling the world and more so India, that it was now taking the lead in building a new regional framework for South Asia.

UNITED STATES

For China’s biggest economic and strategic rival, the idiom “lifting a rock only to drop it on one’s own foot”, is a warning means that when you try to hurt someone else, you end up hurting yourself. In 2025, as the US put more restrictions on Chinese technology and sought to constrain it in the Indo-Pacific, Chinese media and officials used this idiom to say America’s actions would backfire.

They argued the US would damage its own economy and global image while failing to stop China’s growth. By using this idiom, China wanted to show it is calm and patient while the US is acting in ways that will end up hurting itself.

China’s use of idioms in geopolitics is a tool of strategy and soft power. Each phrase allows Beijing to send warnings, project confidence, and shape narratives without open confrontation. Whether signalling its stance towards India, showing solidarity with Russia, or reassuring partners like Pakistan, China uses these ancient sayings to frame its modern ambitions in a way that resonates deeply with its people while signalling its intentions to the world.

In China’s worldview, words are not just words—they are weapons, shields, and tools for building influence in a rapidly shifting global order.

Research Associate at StratNewsGlobal, A keen observer of #China and Foreign Affairs. Writer, Weibo Trends, Analyst.

Twitter: @resham_sng