China seems to have deliberately outsourced its foreign policy messaging to cartoonists.

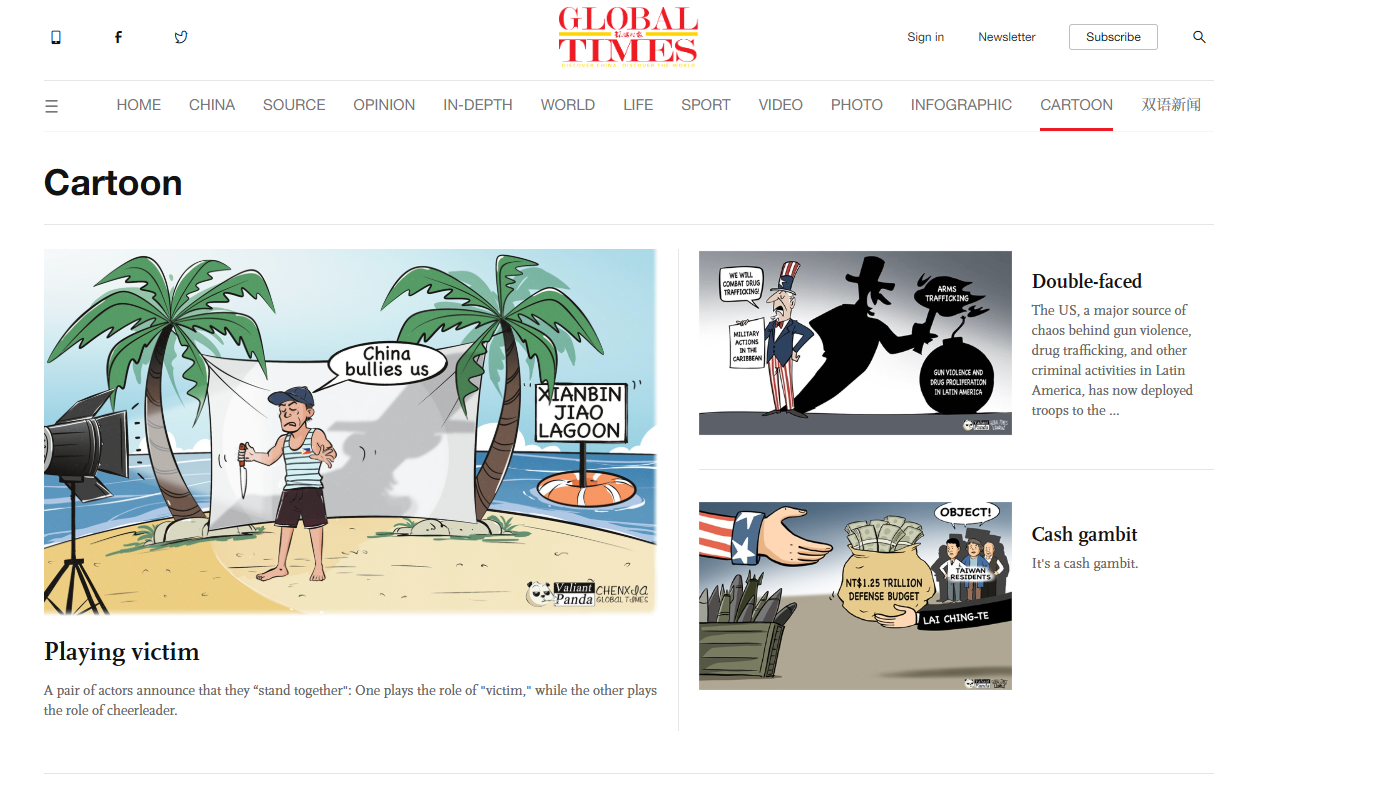

Political cartoons and poster art have quietly been elevated into tools of external propaganda, signalling a conscious shift in how Beijing seeks to shape global opinion. State-run and state-linked outlets such as Xinhua and Global Times now push fresh visuals onto international social media platforms with exuberant enthusiasm, suggesting an institutionalised campaign rather than spontaneous creativity.

Unlike independent media in liberal democracies, which must worry about defamation laws, advertisers, and judges with inconvenient questions, Chinese state media enjoy near-total immunity, granting artists and editors considerable freedom to provoke first and explain later.

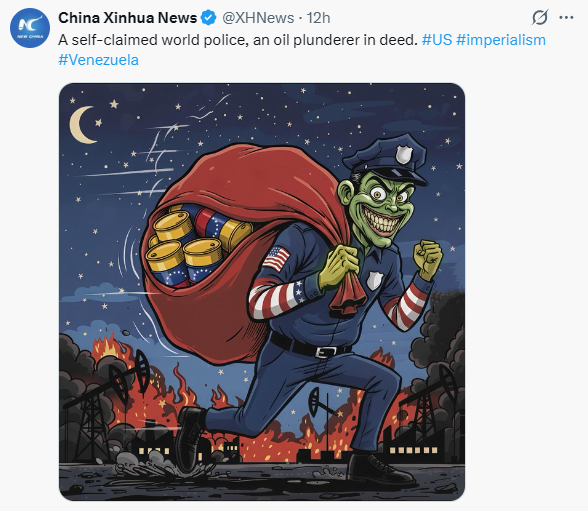

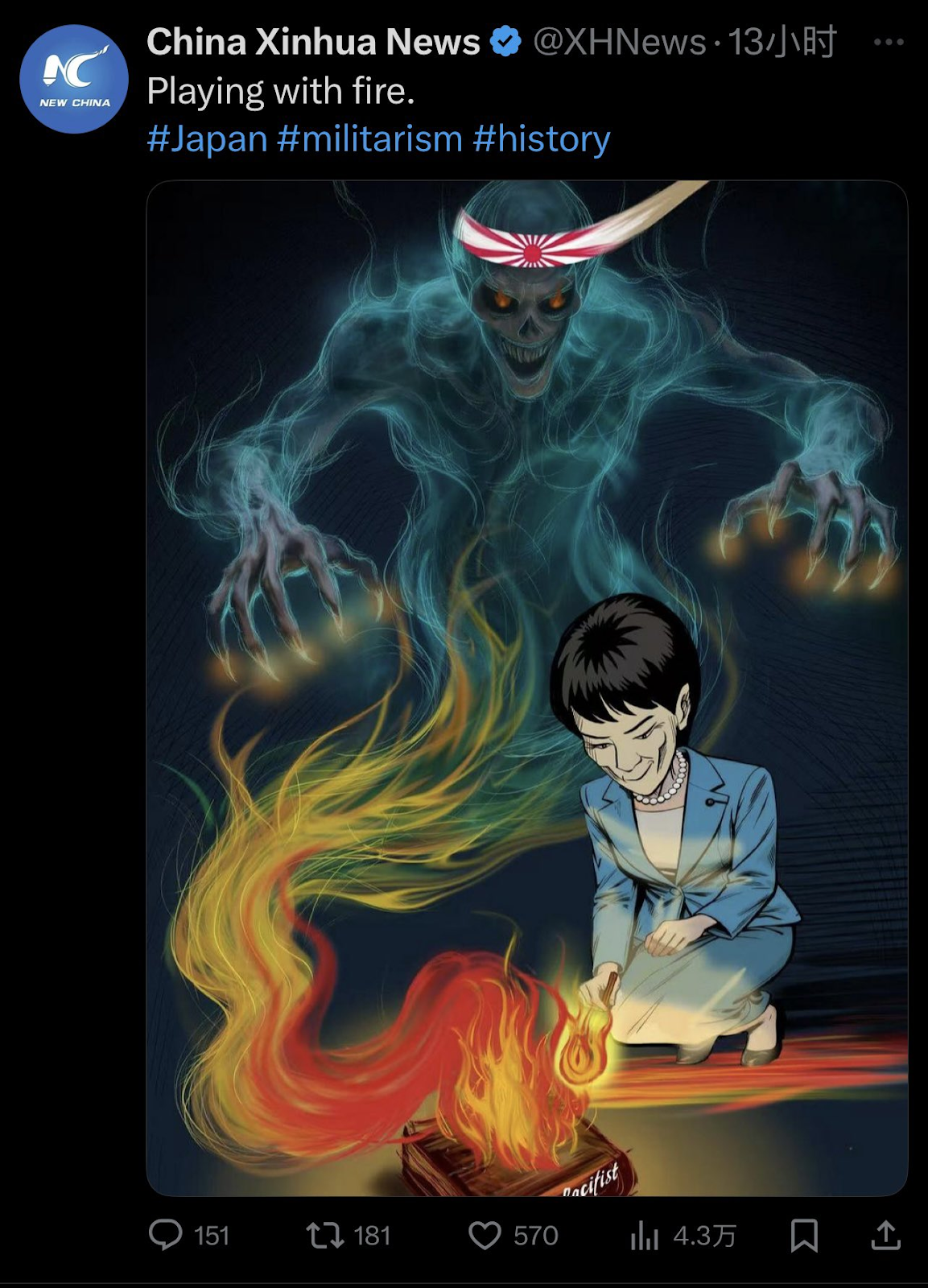

The symbolism is anything but subtle. The United States is almost always Uncle Sam, complete with top hat and moral failings. Asian targets are rendered in simpler visual shorthand: India becomes an elephant, Japan is resurrected through wartime or militarist imagery, and Taiwan is reduced to a child or pawn being dragged around by Washington. The idea is clearly to mock rivals, deny them agency, and impose hierarchy without the inconvenience of naming leaders or governments who might respond.

That cartoons now occupy a formal place in China’s propaganda machinery is not coincidental. Global Times runs a dedicated section titled “Cartoon Commentary,” effectively upgrading visual mockery into editorial doctrine. Xinhua, while avoiding the label, regularly publishes and amplifies poster-style cartoons through commentary and opinion streams, especially on foreign platforms. The result is a steady drip-feed of visual provocation designed less to inform than to ridicule, pressure, and frame adversaries cartoons becoming a sanctioned instrument of information warfare rather than a marginal experiment.

From the U.S. to Japan, and India

The most recent wave followed U.S. military action in Venezuela, after which Chinese state media circulated cartoons portraying Washington as a serial destabiliser of global order. Similar visuals have accompanied PLA exercises such as “Justice Mission 2025,” reinforcing Beijing’s preferred narrative about “external interference” and foreign-engineered instability.

The most recent wave followed U.S. military action in Venezuela, after which Chinese state media circulated cartoons portraying Washington as a serial destabiliser of global order. Similar visuals have accompanied PLA exercises such as “Justice Mission 2025,” reinforcing Beijing’s preferred narrative about “external interference” and foreign-engineered instability.

Japan remains a recurring character in this visual theatre. Chinese cartoons and posters frequently depict Tokyo as sleepwalking back into militarism, sometimes with explicit references to Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi. The framing aligns neatly with Beijing’s long-standing claim that Japan is acting less like an independent power and more like a regional franchise of U.S. strategy. In one poster, PM Sanae appears as a reckless disruptor, captioned: “A politician who attempts to disrupt the game with a dangerous move,” a line that leaves little doubt about who Beijing thinks is responsible for regional instability.

.

India has not been spared. During periods of strain most notably the 2020 Galwan border crisis Indian imagery has featured prominently.

A Global Times cartoon titled “Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the superpower in the world?” showed an elephant in India’s tricolour admiring an exaggerated, muscular reflection. The message was unmistakable: mock India’s ambitions precisely when soldiers were dying on the border. The cartoon was later deleted following international backlash, illustrating both the bluntness of China’s messaging and its sensitivity when reputational costs rise. Similar visuals have surfaced since, particularly during border tensions or moments of closer India–U.S. alignment.

Notably, many of these cartoons circulate primarily on Western social media platforms such as X, rather than Chinese-language websites. The target audience, it seems, is external opinion rather than domestic mobilisation.

Discourse Creation, Not Diplomatic Rupture

According to Cherry Hitkari, Doctoral Fellow at the Institute of Chinese Studies and the Harvard–Yenching Institute, this trend does not represent a rupture in China’s diplomacy. She notes that what is now translated as “propaganda” has never carried negative connotations within socialist systems, where it is understood as education and discourse-setting.

Since the Russia–Ukraine war, many Chinese analysts increasingly see public opinion as a “second battlefield,” one dominated by Western technological reach and media influence. Political cartoons, she argues, are therefore part of a broader hybrid strategy to strengthen China’s “right to speak” and defend what Beijing defines as its national interests. While the tone has become more nationalist particularly for younger audiences the state remains cautious about letting popular nationalism dictate policy. The objective remains discourse creation, not mass mobilisation.

Not everyone is convinced this comes without cost. New Delhi-based China expert Jabin Jacob warns that such cartoons can provoke backlash. Some visuals, he notes, are simply tasteless, inviting diplomatic pushback abroad and uncomfortable questions at home about whether symbolism is substituting for substance.

The Shift From “Wolf Warrior” Diplomacy

This turn toward visual propaganda fits neatly with Beijing’s emphasis on strengthening China’s “international discourse power,” a phrase repeatedly invoked by President Xi Jinping, which aims not to merely respond to events, but to define how those events are framed, debated, and remembered.

In this sense, cartoons represent an evolution from “Wolf Warrior” diplomacy. Where wolf warriors were loud, personalised, and delivered by named diplomats, cartoons are decentralised, deniable, and platform-native. They allow rhetorical escalation without incurring the diplomatic or economic costs that once followed more confrontational official statements. Beijing, seems to believe that a picture provokes more efficiently than a press release.

Why These Cartoons Matter

Platform choice is key. X functions as a hub for policymakers, journalists, defence analysts, and strategic communities. These cartoons are not designed to persuade so much as to insert Beijing’s framing into elite discourse cycles even if the reaction is hostile or mocking.

The growing use of AI-generated visuals has further reduced costs and increased speed, allowing rapid responses to geopolitical developments with eye-catching content. While none of this signals a fundamental shift in China’s foreign policy, it does reflect a greater tolerance for reputational risk in the contest over narratives.

Beyond the United States, India, Japan, and Taiwan, several other countries have been on the receiving end of China’s visual propaganda. Australia famously protested in 2020 after a graphic depicting an Australian soldier threatening a child circulated online. Canada was targeted with mocking visuals during the arrest of Huawei executive Meng Wanzhou, portraying Ottawa as obedient to U.S. interests.

In Southeast Asia, countries such as the Philippines have appeared in posters linked to South China Sea disputes, framed as reckless or manipulated by Washington. European Union states have been depicted collectively as weak, divided, or strategically submissive, particularly over Ukraine and technology controls. Together, these cases underline how Beijing deploys cartoons selectively to pressure governments, frame disputes, and provoke reactions without the inconvenience of formal diplomatic escalation.

Research Associate at StratNewsGlobal, A keen observer of #China and Foreign Affairs. Writer, Weibo Trends, Analyst.

Twitter: @resham_sng