Indian social media watchers will find something disturbingly familiar about the flood of memes, cartoons, taunts and trolling targeting Japan’s Prime Minister Sanae Takaichi. The same was directed at India in the wake of the Galawn clash in June 2020.

Takaichi’s fault was calling for stronger Japanese involvement in cross-strait security, meaning Taiwan’s security, and for China that was unacceptable. At the diplomatic level, Tokyo’s ambassador Beijing was summoned to receive a foreign ministry roasting including a warning against “egregious interference” in its internal affairs.

But the real action was on social media where China’s state machinery turned on the digital propaganda machine: along with insults, taunts and mocking memes, a cartoon showing Takaichi in World War II Japanese military uniform made clear China’s intention to frame the campaiign around Japan’s history of militarism.

It was a signal: the narrative had been set, and the masses were expected to follow. Chinese youth live on social media, and the state knows precisely how to feed them content that blends nationalism with entertainment. Memes, short videos, and snappy insults travel faster than any official statement, creating a climate of digital aggression that soon bled into real-world gestures.

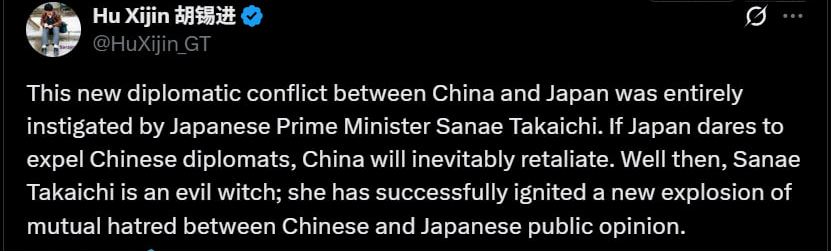

Nationalist “Little Pinks” encouraged users to produce anti-Japan videos, while prominent propagandists added fuel. On 12 November, Hu Xijin China’s most recognisable nationalist commentator took to X (formerly Twitter) to accuse Takaichi of “instigating” the diplomatic row and warned Japan against expelling Chinese diplomats. His framing cast Tokyo as the aggressor and Beijing as the reluctant responder.

China has issued a travel advisory telling its citizens to avoid Japan, referring to Takaichi’s remarks as “erroneous” and claiming they had undermined the atmosphere for people-to-people exchange. The economic fallout was immediate: Japan-related tourism shares plunged, and analysts warned the rift could shave off up to 0.36 % from Japan’s GDP.

Meanwhile, China’s coast guard ships sailed through contested waters around the Senkaku Islands (known in China as the Diaoyu Islands) in a “rights enforcement patrol” a move that Tokyo saw as escalation. The patrols followed Takaichi’s parliamentary comments that a Chinese attack on Taiwan could constitute an “existential threat” to Japan shifting Tokyo away from decades of “strategic ambiguity” on the Taiwan question.

A Chinese man in Tokyo filmed himself waving the national flag in a busy district, boasting online that “the Northeast Chinese arrived first” and tagging Japan’s embassy. While he won some appluse, others saw his stunt as mere posturing.

Since the rift began, Japan-related topics have dominated Weibo’s (China‘s equivalent to X) trending list almost everyday. Discussions spanned foreign policy, military tensions, and historical grievances, a mix that has created a highly concentrated atmosphere of suspicion and hostility.

Takaichi’s remarks were bundled with narratives about Japan “becoming a battlefield,” “reviving militarism,” or “forgetting its defeat.”

Some citizens took the online fervour to theatrical extremes. In Henan, one man staged a parody “military parade” in his backyard wielding a shovel while his wife held their child. He captioned the video (capture of the video below), “I heard that Sanae Takaichi wants to cause trouble, but she’ll have to get past me first.”

These episodes reveal a pattern that Beijing has refined over the years. Whenever geopolitical tension rises, China turns its online ecosystem into a pressure tool. State media sets the tone, influencers echo the message, algorithms reward anger, and nationalists carry the narrative forward.

A similar approach was seen during disputes with South Korea over THAAD, with Australia during the Covid investigations, and with the Philippines in the South China Sea. Each time, Beijing blended propaganda, nationalism and economic signalling to corner the other side.

Research Associate at StratNewsGlobal, A keen observer of #China and Foreign Affairs. Writer, Weibo Trends, Analyst.

Twitter: @resham_sng