China has begun officially issuing the new K-visa to skilled foreign techies, but the knives are already out on social media. One angry user posted: “China belongs to the Chinese people, not just a single government. We firmly oppose the K visa!”

Thousands flocked to the website of the National People’s Congress to register their complaint, and the rush forced the authorities to take it offline rather than see it crash. (Screenshot below) More disturbing is how public anger against the K-visa in China is turning against India even though the visa is open to all skilled foreign nationals.

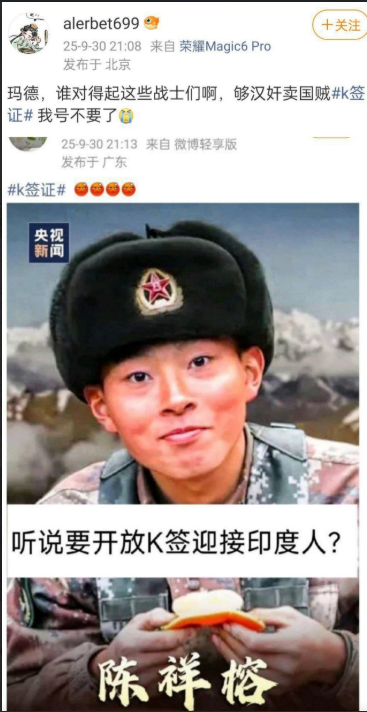

Social media feeds were flooded with posts recalling PLA soldiers killed in clashes with Indian troops. Some users went further, declaring that India was an enemy and insisting that Indians must be barred from entering China under the new visa scheme.

A netizen bluntly wrote: “Enemy India should not enter.” Another recalling the Galwan clashes, warned the authorities directly: “Do you really want our soldiers to die again?” Both comments reflected how opposition to the K-visa has fused with simmering nationalist anger towards India.

Another post targeted India: “Don’t let the thieves (referring to India) be happy,” alongside an image of a PLA soldier killed in the Galwan clashes. “Don’t think I won’t protest this on the streets,” one user warned.

India-themed memes are circulating widely on Weibo.

Many netizens who once mocked Donald Trump as a clown are now praising him as a visionary (given his crackdown on immigrants and H-1B visas that have gone mostly to Indians). When opportunities dry up at home, even the “mad king,” as he was once called, begins to sound like the only one willing to speak uncomfortable truths.

While much of the outrage is couched in terms of nationalism, the sense is it also reflects Chinese racial insecurity or antipathy to the outsider. If immigration debates in the West carried such hostility, they would be branded toxic.

There has been government push-back. People’s Daily dismissed the anger against the K-visa as “wrong in both speech and thought” and “highly harmful.”

The paper argued the visa is vital to address China’s reported shortage of 30 million factory workers. It identified four strands of opposition — those who believe China has enough domestic talent, those fearing job losses, those warning of an immigration crisis, and those citing security risks, rejecting all as narrow, unnecessary, groundless, or lacking confidence.

Criticism of the K-visa is increasingly getting wrapped in historical allegory, which has political implications. The debate is comparing today’s leaders to past emperors who, surrounded by sycophants, lost their grip on reality and collapsed their dynasties.

In a country where dissent is quickly censored and little if no space is allowed for voicing diverse opinions, the K-visa controversy may blow up into something far bigger, which the authorities probably fear the most. It has become a lightning rod for a generation squeezed by unemployment and hardened by a strident state-driven nationalism that demands nothing less than unquestioning obedience.

The concerns and anxieties about China’s future cannot be underestimated. For Beijing, the dilemma is stark: opening the door to global talent may come at the cost of the Communist Party losing trust at home.

Research Associate at StratNewsGlobal, A keen observer of #China and Foreign Affairs. Writer, Weibo Trends, Analyst.

Twitter: @resham_sng