Artificial intelligence is no longer just about chatbots or automation—it is fast becoming a framework through which power itself is exercised.

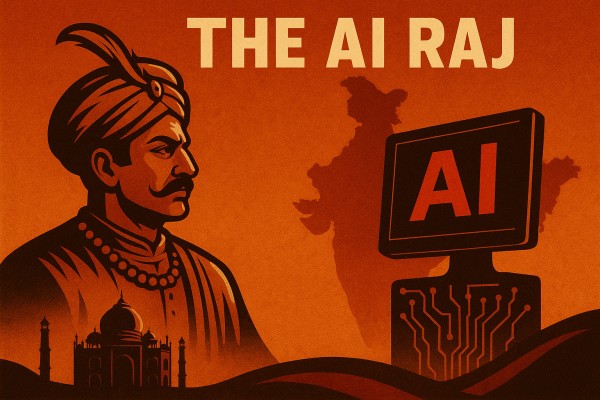

That is the central warning in Allison Stanger’s recent essay, “The AI Raj: How Tech Giants Are Recolonizing Power,” published in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. Stanger draws a stark historical parallel: just as the East India Company began as a trading venture and ended up governing vast parts of India, today’s AI giants are stepping into roles that once belonged exclusively to the state.

Her analysis traces how firms are gradually taking on governmental functions in three critical areas: information, infrastructure, and money. For India, the echoes of history are particularly sharp. If the East India Company’s capture of India began with trade, the “AI Raj” risks beginning with data. And once again, the warning is clear—if sovereignty is ceded in these new domains, reclaiming it later will come at immense cost.

Stanger points first to the power of algorithms, especially in content moderation. Platforms that once claimed to nurture open dialogue are now engineered to privilege engagement at all costs. Truth, nuance, and accountability give way to outrage, misinformation, and viral half-truths.

For India, this is more than a theoretical concern. The country is both one of the largest markets for social media platforms and one of the most politically contested. With hundreds of millions of citizens online, what Facebook, YouTube, or X decides to amplify has direct consequences for democracy. A tweak in the algorithm can tilt electoral discourse, shape public anger, or fuel communal polarisation.

In Stanger’s framing, this is not simply private firms “managing” platforms—it is corporations performing a public function without accountability, in effect deciding the boundaries of speech in the world’s largest democracy.

The second domain she identifies is infrastructure. Satellite constellations such as Starlink and undersea cable systems now form part of the backbone of global communications. Because they transcend national borders, owners can dictate terms in ways governments cannot easily regulate.

India has ambitions of digital self-reliance, but its dependence on private infrastructure is already significant. From cloud services hosted by Amazon and Microsoft to submarine cables laid and controlled by private consortia, much of India’s connectivity rests on decisions made outside New Delhi. Should geopolitical tensions rise, these assets can be withheld, priced strategically, or even repurposed for leverage.

The East India Company once controlled ports and trade routes; today’s AI-era firms control the digital equivalents. For a country that values “data sovereignty”, this is a vulnerability hiding in plain sight.

The third concern lies in the world of money, where cryptocurrencies and stablecoins are reshaping financial ecosystems.

Stanger points to the GENIUS Act in the U.S., which favours stablecoin adoption and exempts key political figures from conflict-of-interest restrictions. Such selective deregulation cements private power in financial governance.

For India, the lesson is timely. The Reserve Bank of India has been cautious, even hostile, toward private cryptocurrencies while experimenting with its own digital rupee. Yet stablecoins pegged to the dollar continue to circulate informally within Indian markets, often beyond regulatory oversight. If these systems grow dominant, monetary sovereignty risks erosion: the “rupee” in digital transactions could become de facto subservient to tokens issued abroad and controlled by firms outside India’s jurisdiction.

Underlying all these domains is what Stanger calls a democratic deficit. Technologies advance and entrench themselves far faster than institutions can respond. By the time laws are debated in parliament or cases reach the courts, dependencies have already formed. In India’s case, the contradiction is stark. The state has pushed for tighter digital regulations—the IT Rules, data localisation mandates, and even proposals for algorithmic oversight.

Yet enforcement lags, expertise is thin, and corporations with global reach can often negotiate exemptions or delay compliance. Citizens, meanwhile, are left with little recourse when their data is mined, their speech curtailed, or their transactions routed through opaque systems. This imbalance of speed and power is the heart of the “AI Raj.” Just as the East India Company’s ships sailed faster than Indian rulers could respond, today’s firms innovate faster than democratic institutions can legislate.

Stanger does not argue that resistance is impossible. She highlights efforts like the European Union’s EuroStack, an attempt to build independent digital infrastructure, and Taiwan’s use of civic platforms like Pol.is to integrate citizen input into policymaking.

These examples show that alternatives exist. For India, the challenge is to translate its ambitions of “Digital India” and “Atmanirbhar Bharat” into tangible autonomy. Aadhaar, UPI, and DigiLocker have already demonstrated that public digital platforms can scale nationally. Extending this model to cloud services, AI training datasets, and even foundational models could reduce dependency on foreign firms.

India’s size also gives it bargaining power. Demanding transparency in content moderation and algorithmic design, as the EU has done, could create accountability where little exists. By accelerating the digital rupee and ensuring it integrates seamlessly with UPI, India can pre-empt reliance on foreign stablecoins. And by strengthening participatory tools that allow citizens to engage with digital policy decisions, India can make governance more resilient.

The historical analogy that runs through Stanger’s essay—the East India Company as a precursor to today’s AI giants—resonates deeply in India. It was not military conquest that first handed power to the Company; it was control of trade routes, revenue systems, and infrastructure.

Over time, these economic dependencies hardened into political subjugation. The “AI Raj” suggests a similar trajectory. If India allows foreign firms to dominate information flows, digital infrastructure, and monetary systems, sovereignty could be hollowed out from within. Unlike in the 18th century, however, this colonisation is not territorial but algorithmic.

India now stands at a pivotal juncture. Its scale, market, and technological talent make it uniquely positioned to resist the consolidation of power by private firms. Yet resistance requires urgency. As Stanger concludes, the risk is not merely private power—it is whether democratic self-rule can survive in the digital age.

For India, with its living memory of colonial rule, the stakes could not be higher. The East India Company began with trade. The AI Raj begins with code. The question now is whether India will allow history to rhyme—or break the cycle before it hardens into destiny.

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.