TAIPEI: Earlier this week, 10 Chinese nationals held on suspicion of espionage by Afghan authorities in Kabul were let off and flown home in a plane chartered by the Chinese government. The terms of their release were not clear although the Afghan government was reported to have demanded a formal apology.

So what were the charges against them? It seems they were in contact with the Haqqani terrorist network and Pakistan’s ISI was playing the mediator. Reports referred to the recovery of arms and ammunition from the homes of some of the Chinese nationals, one of them a woman. Other reports said they were collecting information about the activities of Uyghur militants in eastern Afghanistan bordering China, which would be the provinces of Kunar and Badakshan. The network was also apparently tasked to cover Uyghur settlements in countries neighbouring Afghanistan, which would include Pakistan, Iran and also the Central Asian states of Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan.

It’s interesting to note that the reports mention Chinese spies frequently meeting commanders of various Taliban factions, and their efforts to gather intelligence about Al-Qaida militants.

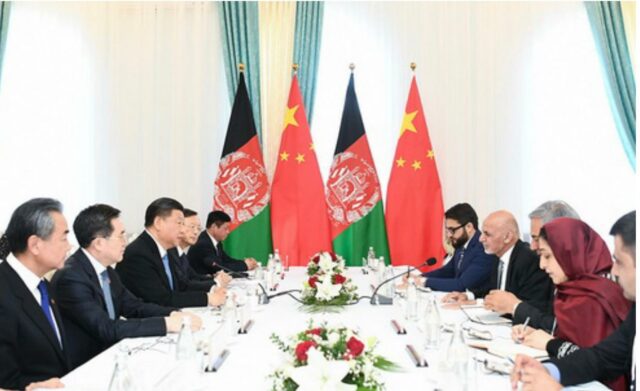

The curious aspect of this entire controversy is how public it went, with Afghanistan’s President Ashraf Ghani intervening to appoint former spy chief Amarullah Saleh (who is now first Vice-President) to probe the case. China is seen as “contributing positively” to the peace process in Afghanistan, which would imply that Kabul should have downplayed the incident or covered it up. But that did not happen.

The sense is the U.S. may have played a role in exposing China’s intelligence activities in Afghanistan. Senior U.S. intelligence officials recently claimed that China was offering money or bounties to non-state actors to attack U.S. military personnel deployed in Afghanistan. It was not clarified if money was offered to the Taliban, Al Qaeda or the Haqqani network. President Trump was briefed about it by National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien and reports said the U.S. was working to corroborate the findings.

The accusations were similar to reports claiming that Russia “sought to pay” militants linked to the Taliban insurgency, to target U.S. military personnel in Afghanistan. Interesting to note that Trump dismissed that report as “fake news” but has not commented upon China.

China’s foreign ministry denied any wrongdoing saying that the charges were meant to “taint China’s image” and damage ties with Afghanistan. “We never started a war with others, not to mention paying non-state actors to attack other countries,” the foreign ministry said.

The incident has renewed attention on China’s intelligence gathering strategy, where intelligence agencies do not rely on the so-called conventional methods of getting information, such as recruiting and paying agents or blackmailing informants. China’s intelligence agencies do not trust or are not willing to work with foreigners. They prefer to rely on ethnic Chinese, including Chinese émigrés and citizens who work and study abroad. In other words, China relies on a huge global social system, a non-professional and informal intelligence network that provides information which reflects Beijing’s priorities in military, socio-political and economic terms. China’s intelligence network in Afghanistan works in this manner.

Precisely because of this, the intelligence gathered can be of a pretty amorphous nature, absorbing all kinds of information through a huge social and interpersonal network. The bits and pieces of information gathered would appear to have no worth but when put together, it appears to have value for the Chinese. They call this the “thousand grains of sand” tactic, where information from various sources when put together provides clues and inferences.

A case in point is a restaurant in Kabul run by one of the women in this “spy ring”. It appears the restaurant is about 10 years old and gathering intelligence was only incidental. In effect, it was a fully functional restaurant which also suggests the woman may not have been an intelligence agent and may have only worked casually for the Chinese intelligence service.

If the U.S. had reason to pressure the Afghan government to publicise the Chinese operation, President Ghani would also have had reason to put a lid on the controversy. He is keen that the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor extends into Afghanistan, so it would make no sense to offend Beijing beyond a point. China, through Pakistan, is also pushing to broaden its influence in the peace talks, touting political inclusiveness, anti-terrorism and good neighbour policy. More to the point, China’s interest in Afghanistan flows from the instability it sees there and the threat it poses to restive Xinjiang province. Add to that, China hopes to profit from various mining leases it has in Afghanistan, so extension of the CPEC across the Durand Line would be of great benefit. But it all depends on when and if peace is restored.

(The author is Secretary General, Taiwan Association of Central Asian Studies. Views expressed in this article are personal.)