NEW DELHI: “Hello, For Employment Advice Please Enter Your Name (Without Last Name), Age, Contact Phone Number. You Will Be Responded By Our Employee During Working Hours From 8:00 To 20:00 Moscow Time Without Days Off.”

That automated reply, (translated from Russian by Google), could easily be mistaken for an innocuous employment pitch. What makes it interesting, however, is that it came in response to a message sent to the WhatsApp number on the website of the Wagner Group, a Russian mercenary outfit with a huge contingent deployed in Ukraine.

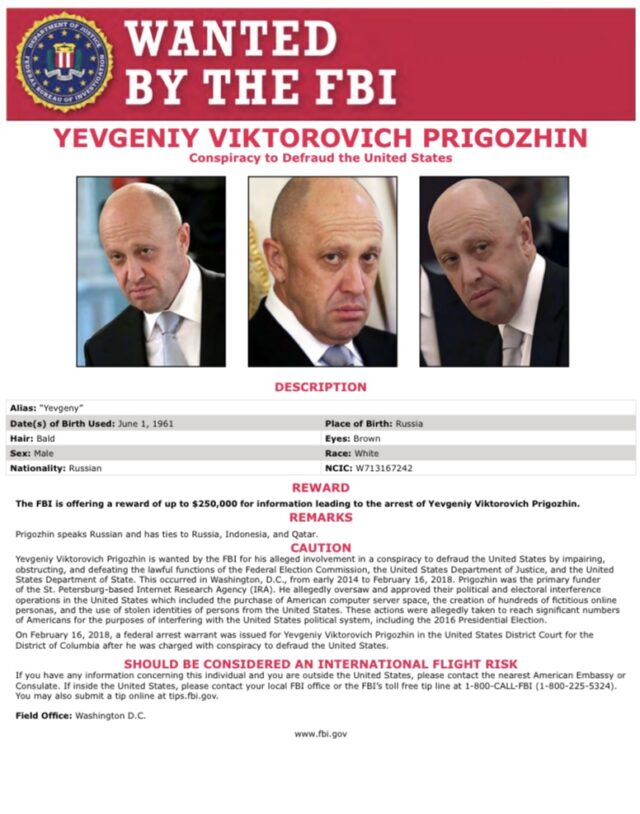

Run by Yevgeny Prigozhin, a billionaire said to be close to Russian President Vladimir Putin, the Wagner Group has an estimated 50,000 fighters in Ukraine, of which around 40,000 are believed to be convicts in Russian jails who were offered amnesty for agreeing to join the group.

In January, the US Treasury Department designated the group as ‘a significant transnational criminal organization’ and, along with the State Department, announced several sanctions on entities linked to the group.

“As Russia’s military has struggled on the battlefield, Putin has resorted to relying on the Wagner Group to continue his war of choice. The Wagner Group has also meddled and destabilized countries in Africa, committing widespread human rights abuses and extorting natural resources from their people,” the Treasury Department release said in a press note.

Days later, top UN-appointed independent rights experts urged authorities in Mali, an African nation plagued by civil strife, to urgently investigate the mass execution of civilians last year, allegedly by government forces and the Wagner Group.

A “climate of terror and complete impunity” surrounds Wagner’s activities in the northwest African country, said the UN experts, which include representatives of the UN Working Group on Mercenaries.

Reports released by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point say the Wagner Group was set up by former Russian Special Forces officer Dmitry Utkin and Yevgeny Prigozhin (who financed it) around 2014, when Russian forces annexed the Crimean peninsula from Ukraine.

Utkin, said to be neo-Nazi sympathiser, joined a Hong Kong registered mercenary group called the Slavonic Corps after retiring in 2013, and fought alongside the forces of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad before returning to Moscow to launch the Wagner Corps with Prigozhin. He was spotted in Crimea during the Russian invasion, and then in the Donbass region, supporting the pro-Russian separatists in the area. He was last seen at a function in the Kremlin to mark Fatherland Heroes Day, and photographed with President Putin. Though reports said he returned to Syria soon afterwards, he has not made any public appearances since then.

Prigozhin, a petty criminal from St Petersburg who was sentenced to 13 years in jail in 1981 for robbery and assault, launched a hot dog stand upon his release in 1990, at a time when the Soviet Union was on the verge of collapse.

By 1995, after acquiring stakes in a supermarket chain, he launched a wine shop and then a restaurant called the Old Customs House on St Petersburg’s Vasilievsky Island, which soon became a celebrity hangout favoured by movie and pop stars, top businessmen, diplomats and mafia bosses, as well as politicians including St Petersburg mayor Anatoly Sobchak and his deputy, Vladimir Putin.

Putin succeeded Boris Yeltsin as President of Russia in May 2000 (after serving as acting president from December 1999), and according a report in The Guardian, often took visiting foreign dignitaries to the Old Customs House and a floating restaurant called New Island, also owned by Prigozhin, who soon became the official caterer to the Kremlin.

He’s been pictured serving food at banquets that Putin hosted for Britain’s Prince Charles (2003), US President George Bush(2006), and even Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Brazilian Prime Minister Dilma Rouseff in 2015 at the Kremlin.

By then, he had also bagged several lucrative government contracts, including providing food to Moscow’s schools and even key units of the Russian Military.

In 2015, the Wagner Group went to Syria as part of Russia’s alignment with the Syrian government forces, earned a reputation for brutality and suffered major losses as well.

Prigozhin was also suspected of setting up a team of cyber-warriors that was accused of interfering in the 2016 US elections and supporting the Trump campaign.

But his abrasive manner towards his colleagues as well as senior military staff that resented his meteoric rise within the system led to a few run-ins. Journalists probing his sudden wealth and ties with the Wagner group were sued, threatened and intimidated, and three that went to Africa to investigate Wagner operations were murdered.

However, soon after Russia launched its military operations in Ukraine, Prigozhin went public about his links with the Wagner group, and started taking credit for a few battlefield successes even as the regular Russian army floundered. He personally took on Russian defence minister Sergey Shoigu, claiming that the Wagner Group was far superior to the regular Russian forces. But when large numbers of his ragtag militia of ex-prisoners too were decimated by Ukrainian forces, Prigozhin released an audio file circulated on the Wagner group’s telegram channel, where he raved and ranted about how the Russian military was not cooperating with his team.

New America, which describes itself as “pioneering a new kind of think and action tank (and) a civic platform that connects a research institute, technology lab, solutions network, media hub and public forum,” has conducted incredibly extensive research on the Wagner Group as part of its ‘Future Frontlines’ program, leveraging data mining, tax identification, corporate registration information, open source maps tools, internet archives, and local media sources.

Ben Dalton, program manager, says it is extremely difficult to slot the Wagner Group under a particular head, given its hybrid functions as a private mercenary army, paramilitary arm of government, extralegal cartel, mafia organization, brand networking phenomenon, and a social movement, as well as its ties with various Russian state and private entities, including energy majors and various government departments.

Noting that even the US used private contractors to support military operation abroad, he said, “We’ve not seen anything like this before.”

However, while the Wagner Group seemed to be embedded within the Russian state security system, he felt that Prigozhin’s reported closeness to Putin might be somewhat exaggerated, and that he probably had to go through several underlings in the Kremlin rather than being a direct confidante of the President.

Also, Prigozhin might see this as a unique opportunity to position himself as a leader of the far right ultranationalist movement in Russia, and is hence trying to become the face of an emerging mass movement, he said.

However, with the increasing number of casualties and deserters from his team and rumours about standardising the Russian deployment in Ukraine, he could be feeling a bit desperate, he felt. “He’s probably losing some of his influence.”

Sergey Sukhankin, Senior Research Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation, a Conservative defence policy think headquartered in Washington DC, believes the main reason for Prigozhin going public about his ties with Wagner was his “realization of the seeming indispensability of the Wagner Group for Russia`s war effort against Ukraine. Apparently, he made this move to boost his role and, perhaps, even political ambitions within Russia`s so-called ‘power vertical’. He tried to seize the moment and—given problems experienced by the Russian regular army—go public as a sponsor/head of the Wagner group.

As for his public tirade about not getting support from the Russian military, he said: “I believe this is a continuation of this previous strategy based on two pillars: first, diminishing the role of the Russian army by accusing its leadership of being unskilful and indecisive; second, boosting his own image as an indispensable force and a person who knows and understands public rage caused by unprofessionalism of the Russian Ministry of Defence.”

However, he warned that “this may lead to tragic consequences for Prigozhin. The Russian defence ministry is now practically in charge of recruiting fighters from prisons (“volunteers” in Russian official narrative) and Prigozhin is becoming redundant. Moreover, his offensive accusations of Russia`s military-political leadership—quite dangerous for Putin—and attempts of garnering political weight will not be forgotten. It is very likely that once Prigozhin is no longer needed, the regime might do away with him easily.”

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.