In 2010, on the eve of Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao’s visit to Delhi, Beijing made a quiet but symbolic announcement: the last county in China without road access — Metok, nestled deep in the eastern Himalayas — would soon be connected to the outside world. It wasn’t just about infrastructure. It was a statement of intent.

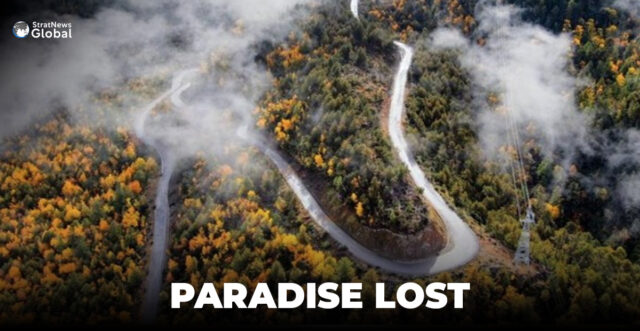

In 2013, the road was real — a superhighway carved through one of the world’s most ecologically sensitive and spiritually significant regions. On the surface, it’s a triumph of engineering. But beneath the tarmac, a more troubling story flows — one of environmental precarity, cultural erasure, and escalating geopolitical tension, all carried by the currents of the Yarlung Tsangpo River, known downstream as the Brahmaputra.

Metok — or Pemakoe, as Tibetans know it — is no ordinary patch of earth. It’s a sacred valley revered in Buddhist tradition, believed to be a hidden paradise protected by the goddess Dorje Phagmo. For centuries, its isolation was a shield, preserving rare biodiversity and spiritual sanctity. But that remoteness has now been breached — not just by roads, but by a vision of “development” that sees rivers not as lifelines, but as levers of control.

At the heart of this vision is a $137 billion megadam that China is planning near the Great Bend of the Yarlung Tsangpo, just upstream from the Indian border. Once completed, it will surpass even the Three Gorges Dam in scale. For Beijing, it’s a renewable energy dream. For New Delhi and Dhaka, it’s a nightmare in the making. Renowned Tibetologist and China-watcher Claude Arpi, however, is not sure that China really intends to build a big dam on the Brahmaputra, as Tibet is seismically active. ‘It may build a series of hydel power projects instead,’ he said in an interview to Down to Earth.

But either way, nations downstream will be impacted. Unpleasantly.

There is no water-sharing treaty between China and its southern neighbours. The Brahmaputra supports the livelihoods of millions in India and Bangladesh — not just for agriculture and fishing, but for flood forecasting and disaster preparedness. Without guaranteed hydrological data or legal recourse, downstream countries are at the mercy of upstream decisions. This isn’t just a technical problem. It’s a strategic one.

And Beijing knows it. During the 2017 Doklam standoff between Chinese and Indian troops, China suspended its transmission of river data to India — a subtle but potent form of pressure. In the Himalayas, water is no longer just a resource. It is a weapon, a bargaining chip, and a test of how environmental cooperation can be quietly sacrificed on the altar of geopolitics.

China’s aggressive dam-building isn’t only about control; it’s also about desperation. The country’s water crisis is deepening. Glacial melt is accelerating. Groundwater reserves in the north are drying up. Pollution has rendered large swathes of water undrinkable. Faced with this crisis, Beijing is increasingly turning to transboundary rivers to meet its needs — and to impose its will.

India is responding in kind. In Arunachal Pradesh, the government has proposed the $13.2 billion Siang Upper Multipurpose Project, a massive hydroelectric dam that would store nine billion cubic meters of water and generate 11,000 megawatts of electricity. On paper, it’s a counter to China’s upstream ambitions. On the ground, it’s a catastrophe in waiting.

At least 20 villages will be completely submerged. Nearly two dozen more will be partially inundated. Thousands of residents — many of them Indigenous — face displacement. Environmentalists warn of seismic risks, biodiversity loss, and irreversible damage to riverine ecosystems. Local opposition is mounting, but in the grand chessboard of Asian geopolitics, such voices are often drowned out.

What’s unfolding in the eastern Himalayas is a slow-motion conflict with no declared war, no uniformed troops, and no dramatic flashpoints. Just concrete. Just rivers rerouted and valleys flooded. Just the gradual suffocation of sacred places and fragile communities under the weight of “national interest.”

The stakes go beyond India and China. The Himalayan watershed feeds not only the Brahmaputra but also rivers that nourish Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, and parts of Southeast Asia. As the so-called “water tower of Asia,” Tibet’s rivers are the arteries of a region already strained by climate change, urban expansion, and food insecurity. Weaponising them risks destabilising an entire subcontinent.

So, what should be done?

First, regional diplomacy must prioritise water governance. An Asian equivalent of the Indus Waters Treaty or the Mekong River Commission — imperfect though they are — is urgently needed. Without formal agreements on data sharing and environmental impact, mistrust will fester and crisis will creep. While China is most unlikely to agree, the pressure must continue.

Second, both China and India must reassess the costs of their hydro-ambitions. Renewable energy is critical, but not at the expense of entire communities and ecosystems. Smaller-scale, decentralised alternatives deserve more attention. So does listening to the people most affected. It is important to note that very few people are affected in sparsely populated areas of Tibet.

Finally, we must stop viewing these regions as blank canvases for grand infrastructure. Pemakoe is not just a valley. It is a sanctuary, a storehouse of cultural and ecological memory. Its remoteness was not a problem to solve — it was a gift to protect.

Because when paradise is paved, no one escapes the fallout — not pilgrims, not farmers, not future generations.

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.