Breakfast –an omelette, a sausage, a bun, butter and cheese, some sliced fruits – was served at 2 am.

The cabin lights were dimmed soon afterwards, and from the window, one could see the clouds reflecting the moonlight and the red blinking wingtip light of the Airbus 321 LR (Long Range) as it ate up the miles with a quiet, confident hum. At 4.15 am, Air Astana’s flight KC 964 from New Delhi touched down at Almaty, Kazaksthan, having covered some 1625 km in just under four hours.

Touchdown at dawn

The international airport at Almaty, the former capital of the largest Central Asian country, (and the 9th largest in the world) has a quaint old-world charm, despite being the busiest airport in the region. The people who had briefed me in Delhi had mixed up visa on arrival with visa-free, so I was a bit surprised when I was waved through immigration with just a tiny stamp on my passport.

Barely 20 minutes from the time I landed, I was in the domestic terminal next door, waiting to board the flight that would take me to the new capital, Astana, another 1,000 km north. That was where the 24th Summit of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation was scheduled to begin the next day.

Having missed it while landing due to the pre-dawn darkness, I was unprepared for the breath-taking sight of snow-capped peaks which seemed close enough to touch, glittering in the clear early-morning light as I boarded the bus taking me to the plane to Astana.

Almaty International Airport

If Almaty was quaint and old fashioned, Astana, where I landed an hour and half later, was the exact opposite. After a slightly embarrassing moment when upon asking whether I needed a visa, a bemused official told me that this was a domestic airport and hence had no passport control office, I was outside the terminal at 7.30 am.

A tall tout approached me, asking me if I needed to change money, and seemed disappointed to learn that I was not from Pakistan. The airport seemed a bit deserted, with only a few taxis on the kerb, with their drivers chatting in a corner. One of them insisted he was registered with the government, and that I could check the rate with the hotel before I paid him.

They renamed the city, but the airport is still called Nursulstan Nazarbayev

The ride to Hotel Jumbaktas took about half an hour along the Qabanbay Batyr Ave, dotted with large mosques and small farms till we reached the main city.

The gleaming blue and white façade of the hotel matched the modern high rises and other buildings of myriad shapes, sizes and colours, which competed with Soviet style square blocks.

A flat dome design which resembled a crashed spacecraft seemed to be fairly popular, with both the upmarket Hilton Astana, where all the visiting heads of state including Russian President Vladimir Putin and China’s supreme leader Xi Jinping were put up, as well as several petrol stations and a couple of shopping malls adopting it.

The Hilton, Astana. Back to the Future.

Inside Jumbaktas, however, the fading paint on the walls and the ancient upholstery of the sofas in the lobby gave away the hotel’s age. The young man at the counter didn’t speak English, but used a translation app on his phone to explain that it was not even 9 am, and my booking was from 2 pm. No amount of pleading and cajoling worked.

When I asked if I could leave my suitcase and go look around the city, I was told that since there were some other guests expected, I might face further delays in getting a room if I was not present as and when they became available later in the day.

As I parked myself on a faded sofa near the desk, I was politely informed that the free WiFi did not even need a password. I promptly called the embassy seeking their intervention, only to be told that while the hotel was among the three listed by them owing to their proximity to the media centre, they did not have any particular ‘arrangement’ or leverage with this one.

A young lady who came to the front desk a while later helpfully explained that I could always ‘rejuvenate’ at the spa in the hotel while I waited, for a mere 40 to 50 U.S. dollars, or drink myself silly at the bar. I demurred.

When I finally did get the room around 12.30 in the afternoon, my irritation was somewhat eased by its sheer size, and the view of the city skyline from the window.

A room with a view

But I had wasted enough time, so a quick shower and change later, I went down to ask if I could get a cab to take me to the Expo pavilion, where I had lined up an interview with Doulat Kuanyshev, a former ambassador to India and Israel, now an expert with Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA), a multi-national forum for enhancing peace, security and stability in Asia.

The young lady at the desk gave me a local sim, but said I would have recharge it before use. Since that involved a rather complicated process of texting codes and passport numbers back and forth in Russian, I postponed it and took a hotel cab to the centre, dominated by the Nur Alem, said to be the largest spherical building in the world, with a diameter of 80 and height of 100 metres.

Former President Nursultan Nazarbayev, who ruled Kazakhstan from the time of its Independence in December 1991 till he stepped down in March 2019, shifted the capital to Astana from Almaty in 1997, ostensibly because the latter was creaking at the seams in terms of infrastructure and was built on an earthquake-prone zone.

But others cite Almaty’s proximity to the border with China in the west, rising Islamic fundamentalism in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Afghanistan to the south, and Nazarbayev’s need to strengthen his hold in the northern region, where there is a large population of Russians (like the Oblasts in Ukraine), as more plausible strategic reasons.

Size Matters

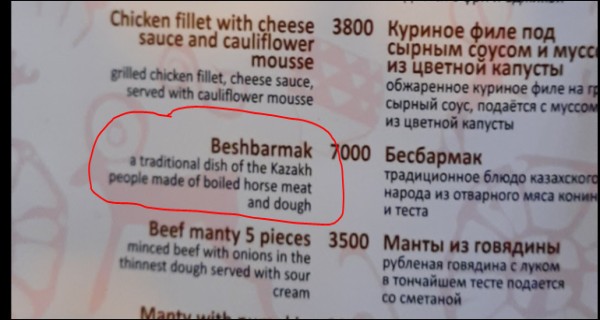

With a population of just 20 million, Kazaksthan has one of the world’s lowest population densities—less than 6 people per square kilometre. (India has 439 per sq km). While locals joke that their country has more horses than people, statistics indicate that there are about 4 to 5 million horses in Kazakhstan, and counting. Horse meat is a staple Kazakh diet, often served boiled with noodles as beshbarmak, and kazy, a type of sausage.

The Kazakh currency is Tenge. One Indian Rupee is about 6 Tenge, or 0.0021 USD

The Kazakh currency is Tenge. One Indian Rupee is about 6 Tenge, or 0.0021 USD

Astana (which basically means ‘Capital’) can be compared favourably with any modern western city in terms of facilities and infrastructure. Traffic is extremely well regulated, and the streets are spotless, with no sign of litter. Young girls in miniskirts walk around visiting pubs and bars which stay open well past midnight. And at a late-night diner, when I asked for what appeared to be pepperoni pizza, the attendant apologetically explained that it was beef, since they didn’t serve pork.

Nazarbayev, born to devout Sunni parents, grew up to become a card-carrying comrade, and aggressively promoted intra-ethnic – and intra-religious – harmony, something that his successor Kassym-Jomart Tokayev continues to uphold.

The massive Assumption Cathedral –Not to be mistaken for the much larger Russia-operated Baikonur Cosmodrome, some 1150 km southeast of Astana

So, while predominantly a Muslim nation, no one wears their religion on their sleeve, and apart from mosques, the country also hosts churches and synagogues like the Beit Rachel, the largest in central Asia, and the massive Assumption Cathedral, which can host upto 4000 people.

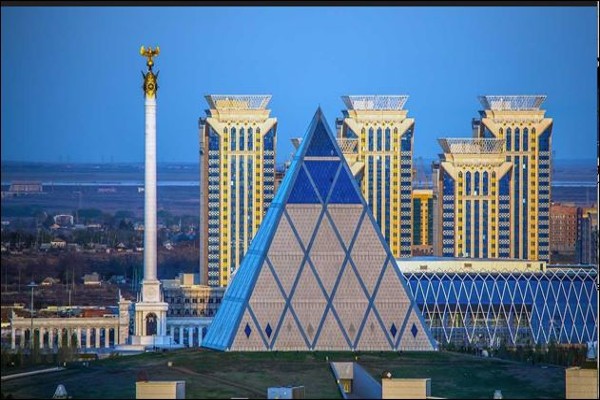

The next day, I took an early-morning ride to the Palace of Peace and Reconciliation, also translated as the Pyramid of Peace and Accord, where the main SCO summit was being held.

Steel Giza. Photo Courtesy Kazakhstan Tourism

Built as a national spiritual centre and event venue, the 62-metre-high pyramid is an architectural wonder. Its steel frame built to withstand Astana’s extreme climate, which ranges from 40 degrees in the summer to -40 degrees in the winter, making it one of the coldest cities in the world, and the second-coldest national capital in the world after Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia.

Presidents Xi and Putin were obviously the main focus of attention at the summit, which had journalists from over 30 countries in attendance. For us Indian journalists, however, the meeting between External Affairs Minister Dr S Jaishankar and China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi took precedence.

This meeting, however, turned out to be a damp squib when the readouts issued by the two sides reiterated completely different perspectives that have plagued the relationship since the Galwan Valley clash of June 2020.

As a photographer quipped later, ‘I thought winter in Astana was cold. ‘

Two remarks by a Kazakh journalist I met at the summit are perhaps worth mentioning.

One, that their government had instructed everyone involved not to let bilateral relations overshadow the multilateral summit.

And two, that while Kazakhstan and India enjoyed warm and friendly relations since the Soviet era and perhaps even earlier, the two nations were distant neighbours at best. China, on the other hand, shared a direct land border with Kazakhstan, and was one of the biggest investors in the country. Enough said.

As soon as the summit was done and dusted, we rushed out to take a bus to the city to avoid the gridlocks caused by the VVIP traffic, as the heads of state headed home. But we were too late, and it was almost late evening by the time we crossed the Ishim River into the city.

Security for the summit was tight but light

The next morning, I left the hotel at 4.30 am, after a quick breakfast provided by the thoughtful management, to take a 6 am flight to Almaty. Only to discover that the connecting flight to New Delhi, scheduled to leave at 10 am, was delayed till 1 pm.

I spent those hours gazing at the pristine mountains, and browsing through the large duty-free section, well-stocked but expensive. When I asked why each item had two prices marked, one at least 20 per cent higher than the other, I was told that anyone travelling to Russia had to pay that premium.

I also stumbled upon a corner of the airport which looked out onto what appeared to be a helicopter graveyard.

Is this where all the broken choppers go?

When I returned to the gate for the flight, I found a loud, boisterous crowd of north Indian tourists harassing a solitary Astana Airways attendant serving coffee and juice to passengers ‘inconvenienced’ by the delay.

Things got worse once we boarded the aircraft, with some of them verbally and physically abusing the air hostesses, shouting loudly at each other while trying to forcibly stuff their large pieces of luggage into the overheard bins.

It took a burly tattooed man with a Russian accent to step up and threaten to send some of them home on stretchers before the bedlam eased, although the muttering of abuse in Hindi continued.

Almaty Salaam

As I sat and looked out the window to bid goodbye to the mountains, I fervently wished the man had actually carried out the threat. A few hours later, I was back in New Delhi.

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.