On an overcast morning, Nurun Nabi loads bamboo poles and tin sheets onto a wooden boat. His home, built just a year ago on a fragile island in the Brahmaputra River in Bangladesh, is on the verge of being swallowed by water.

It is the second time the farmer and father of four has had to move in a year.

“The river is coming closer every day,” Nabi said, his voice tight with exhaustion. “We are born to suffer. Our struggle is never-ending. I’ve lost count of how many times the river took my home.”

Nabi, 50, has no choice but to move to another char – a temporary island formed by river sediment. His rice and lentil fields are already gone, claimed by the advancing current of the Brahmaputra River, which originates in the Himalayas and flows through China and India before reaching Bangladesh.

“I don’t know what awaits us there in the new home,” he said, looking towards the wide brown river. “If I’m lucky, maybe a few years. If not, maybe a month. This is our life.”

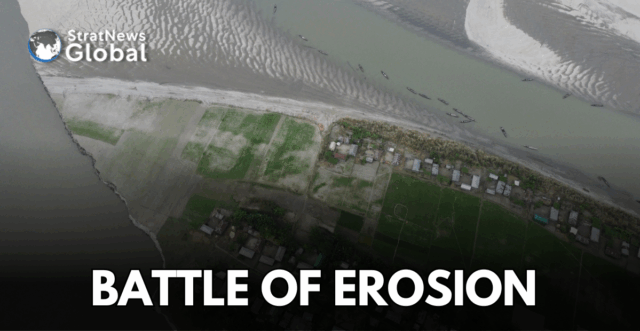

Land That Disappears Overnight

Every year, hundreds of families in northern Bangladesh’s Kurigram district face the same fate. As riverbanks collapse, people lose not only their homes but also their land, crops, and livestock. The Brahmaputra, Teesta, and Dharla rivers — once lifelines for millions in Bangladesh— have become unpredictable, eroding land faster than ever before.

The chars — sandy, shifting islands scattered across the country’s northern plains — are among the most fragile places in Bangladesh. Families rebuild again and again, only for the river to take everything they have.

“The water comes without warning,” said Habibur Rahman, a 70-year-old farmer who has lived on several chars. “You go to sleep at night, and by dawn, the riverbank has moved. You wake up homeless. There is no peace in our lives.”

As the world’s eyes turn to Brazil, the host of the U.N. climate summit from November 10 to 21, Bangladesh’s struggle offers a sobering message for global leaders. The country is often praised as a model of resilience — building embankments, improving flood forecasting, and pioneering community-based adaptation. But without stronger international support and climate finance, those efforts will fall short.

“People here are paying the price for emissions they never made,” said Ainun Nishat, a water resource and climate change specialist. “If COP30 means anything, it must deliver real funding for loss and damage and help vulnerable nations like ours protect lives and land before it’s too late.”

Climate Change

Scientists say what is happening in Kurigram, Bangladesh, is climate change made visible, as the melting of the Himalayan glaciers that feed the Brahmaputra and Teesta rivers accelerates.

“We are seeing rapid glacial melt, almost double the rate of the 1990s. Extra water is flowing downstream, adding to already swollen rivers,” said Nishat, the climate change specialist.

At the same time, the monsoon has grown more erratic — arriving earlier, lasting longer, and falling in intense, sudden bursts. “The rhythm of the seasons has changed,” Nishat said. “When it rains, it rains too much, and when it stops, there are often droughts. This instability is making erosion and floods far worse.”

He added that Bangladesh contributes less than half a per cent of global carbon emissions, yet suffers some of the most serious consequences of climate change.

The World Bank estimates one in every seven Bangladeshis could be displaced by climate-related disasters by 2050.

(with inputs from Reuters)