Part I: Promises Vs. Power: China’s Mega Dam Contradiction

India’s response to China’s mega dam project on the Yarlung Tsangbo (as the Brahmaputra is known in Tibet) near the Great Bend, where the river curves sharply before entering India, remains mired in internal contradictions.

Officials have proposed two key storage dams in Arunachal Pradesh — at Yinkiong and downstream toward Upper Siang — with a combined storage capacity of 9.2 billion cubic metres. These would help store excess monsoon flow and act as shock absorbers for sudden upstream discharges.

But these plans, as noted by a senior Indian specialist on water resources, remain mostly on paper. The upstream Chinese dam is already under construction.

Ironically, the very risks India worries about from China’s dam are mirrored in opposition to its own: fragile terrain, seismic vulnerability, and local livelihoods. The 510-metre FRL planned for the Indian dam would submerge significant portions of Yinkiong and impact defence infrastructure, requiring major relocations.

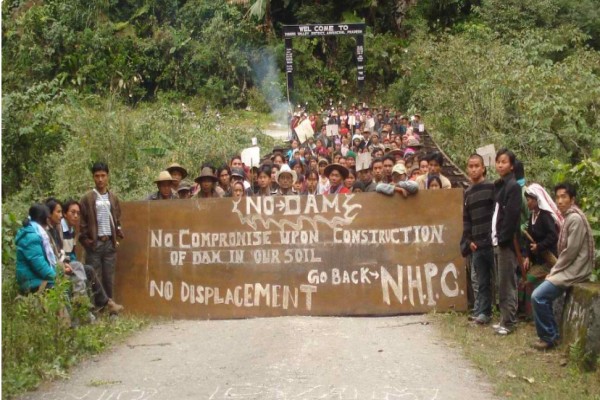

Local communities have strongly opposed these projects, citing ecological risks and displacement. Past efforts, such as the Upper Siang multipurpose project, have been shelved for similar reasons.

The state’s location in a seismic hotspot further complicates matters. Memories of past disasters, including the 1950 Rima earthquake and the 2017–2018 landslides upstream in Tibet, have made the population more wary of massive infrastructure projects. While China pushes ahead with its mega project in the same vulnerable terrain, India must contend with a different reality — one shaped by democratic norms, legal checks, and people’s voices.

Events in 2017 and 2018 have only heightened these concerns. The landslides and earthquakes upstream turned the Siang black and blocked flows, revealing the fragility of both the river system and India’s monitoring capabilities.

Even as China builds aggressively in this high-risk terrain, India must weigh its response more cautiously. The memory of past disasters — the 1950 quake, the 2017 landslides, and the 2018 river blockages — makes local resistance both grounded and legitimate.

India has established an extensive network of automated river sensors at Tuting, Yinkiong, Pasighat, and other sites. These stations allow for near-real-time tracking of water levels, turbidity, and flow. But they are early warning systems, not preventive mechanisms. With the termination of the data-sharing agreement by China in 2023, India now flies blind to upstream developments unless they become immediately visible — or catastrophic.

India’s actionable paths are limited but not absent. Several strategic, diplomatic, and technical options could bolster India’s position:

- Expedite Domestic Infrastructure: Responsibly fast-tracking the Yinkiong and Upper Siang projects is essential, but it must be done in consultation with local communities, using environmentally sensitive designs, seismic risk modelling, and compensation mechanisms.

- Enhance Bilateral and Trilateral Mechanisms: India could push for the revival of hydrological data-sharing mechanisms with China — or propose a new framework involving Bangladesh. The absence of a basin-level institution like the Mekong River Commission makes the Brahmaputra basin vulnerable to unilateral actions.

- Regional Coordination with Bangladesh: India and Bangladesh share strong ties, but Brahmaputra water flows remain a delicate subject. India can initiate joint assessments with Dhaka to determine potential downstream impacts and present a united front in discussions with Beijing.

- International Advocacy on Ecological Risk: India can raise awareness in UN forums, the World Bank, and climate conferences, emphasising the ecological and geological threats posed by mega infrastructure in the Himalayas. Xi Jinping’s pledges at the 7th Tibet Work Forum offer diplomatic leverage to highlight the contradiction between words and actions.

- Invest in Resilience and Forecasting Systems: India must upgrade its flood forecasting systems and invest in resilient infrastructure downstream in Assam and West Bengal. This includes strengthening embankments, improving reservoir management, and modernising irrigation systems.

- Use Satellite Monitoring for Transparency: With bilateral data unavailable, India should expand use of remote sensing and AI-driven modelling to monitor upstream activity in Tibet. Partnering with space-faring nations and agencies (like ISRO, NASA) can help maintain a credible, independent information flow.

- Public Diplomacy and Strategic Messaging: India can also shape global narratives through research institutes, media, and strategic forums — highlighting how the Great Bend project could destabilise fragile ecosystems and jeopardise millions of lives downstream.

India’s challenge lies in asymmetry. While China moves swiftly, India is held back by constitutional safeguards, environmental laws, and democratic resistance. That these are strengths, not weaknesses, should be India’s narrative — but they also demand better governance and faster action.

It is also a reminder that water, once seen as a benign natural resource, is fast becoming a strategic asset. Hydrological dominance in the Himalayas could offer political leverage, economic security, or a trigger for conflict.

India cannot match China dam for dam — nor should it attempt to. But it must prepare to safeguard its interests through a mix of infrastructure, diplomacy, resilience, and regional alliances. The disasters of the past — and the dam being built today — offer ample reason to act before the next crisis arrives.

Whether or not China acts responsibly, India must. And that means moving from reaction to readiness — before the next flood, quake, or landslide turns warning into catastrophe.

Part III: Strategic Waters: India’s Dam Dilemma in Arunachal Pradesh

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.