NEW DELHI: Being two ancient civilisations, India and China have known each other almost since the beginning of time. Even the mighty Himalayas could not prevent the two civilisations from getting acquainted with each other. Contacts between the two countries go back to 2nd century BC though China/Chinese related references can be inferred in earlier Indian literature too. Buddhism came to China from India in 1st century AD. Thenceforth, many Indian monks and scholars travelled to China. The first abbot of Shaolin monastery, Batua, and the founder of Zen Buddhism, Bodhidharma, are said to have travelled to China from India. Chinese monks and scholars travelled to India, stayed and studied in India, especially at Nalanda University. Fa-Hsien, (AD 399-414), a Chinese monk, visited India in AD 402. He stayed in India for 10 years and translated many Sanskrit Buddhist texts into Chinese on his return. The silk route provided a conduit for trade and economic links between India and China. The Chola kings had trade links and a secure sea route to China. Throughout history, there are several examples of positive linkages between India and China.

Independent India started off with this tradition of friendship with China. Jawaharlal Nehru had a grand vision of a resurgent Asia in which friendly ties between India and China would be based on the principles of peaceful coexistence or Panchsheel. The two countries established diplomatic relations on 1 April, 1950; India being the first non-socialist country to establish relations with the People’s Republic of China. High-level visits were exchanged between the two countries. The Hindi-Chini Bhai Bhai (Indians and Chinese are brothers) sentiment characterised the relationship. This did not last very long as China built a road in Aksai Chin and moved into Tibet. Even after Nehru conveyed to the Chinese leaders that India had no political territorial ambitions in Tibet and sought only the continuation of traditional trading rights, differences over the border emerged, eventually leading to a short but disastrous border war in October 1962.

The mistrust generated by the 1962 war continued to haunt the psyche of an entire generation in India. Neighbours have to learn to live with each other. Successive leaders from late 1980s onwards made an effort to get past the old misgivings, to bring the two countries closer and develop economic linkages, even as efforts continued to resolve the ticklish border issues. Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi visited China in 1988, beginning the improvement in bilateral relations. In 1993, an agreement on the Maintenance of Peace and Tranquility along the Line of Actual Control on the India-China border areas was signed during Prime Minister PV Narasimha Rao’s visit. During the visit of Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee in 2003, India and China signed the Declaration on Principles for Relations and Comprehensive Cooperation and decided to appoint Special Representatives (SRs) to explore the framework of a boundary settlement. A special fillip to these efforts was given by PM Narendra Modi. Following the visit of Chinese President Xi Jinping to India in 2014, PM Modi visited China in 2015, followed by President Pranab Mukherjee in 2016. PM Modi and President Xi held the first informal Summit in Wuhan in April 2018. They also met on the margins of BRICS, G20 and the summit meetings of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). These efforts continued despite the standoff in Doklam in 2017.

In June this year, India’s confidence in China was rudely shattered by the Chinese aggressiveness in eastern Ladakh. Multiple rounds of talks later, we still don’t see the restoration of status quo ante. Some hold that the Chinese have no intention of vacating the space they moved into; that there is too much at stake for China: water sources, linkage between Xinjiang and Tibet and safety of Karakoram highway.

This is where India’s dilemma lies. It is apparent that making concessions to China in the hope of generating goodwill is not necessarily seen by China in the intended spirit. It is more likely seen as a sign of weakness. China’s increasing assertiveness in recent years in its own neighbourhood, be it the East China Sea or South China Sea, or its approach to Taiwan, indicate a disregard for international opinion. Chinese activities in India’s neighbourhood have intensified and should no longer be ignored. Yet, as a peace-loving country, India has always believed in peaceful resolution of issues.

A solution to the conundrum has to be found through some out-of-the-box thinking. Chinese prosperity has been built on large-scale production of goods that are sold largely outside China. Even with its massive technological advances, Chinese factories need markets outside their own territory to continue their economic trajectory. Chinese infrastructure projects like China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), including Gwadar Port, Belt and Road Initiative and others seem to be driven by the Chinese need to have ready access to export markets for its products. This may sound innocent enough but even if the strategic aspects of these projects are overlooked, success of these projects would lead to the economic subjugation of the rest for China’s benefit. One cannot think of a better example of neo-colonialism.

The process of decoupling from China would not be easy. Globalization has led to enormous interdependence amongst countries. Moreover, Chinese capital has found its way to various parts of the global economy, including the Indian economy. India is one of the world’s largest markets. There is an urgent need to undertake a thorough analysis of the sections of our market that can be ring-fenced from Chinese entry and sway. We should also make a similar effort with other major powers and markets. Due to the Chinese aggressiveness in its neighbourhood and its piratical economic approach to nations across the globe, there is increasing desire amongst nations to take back control!

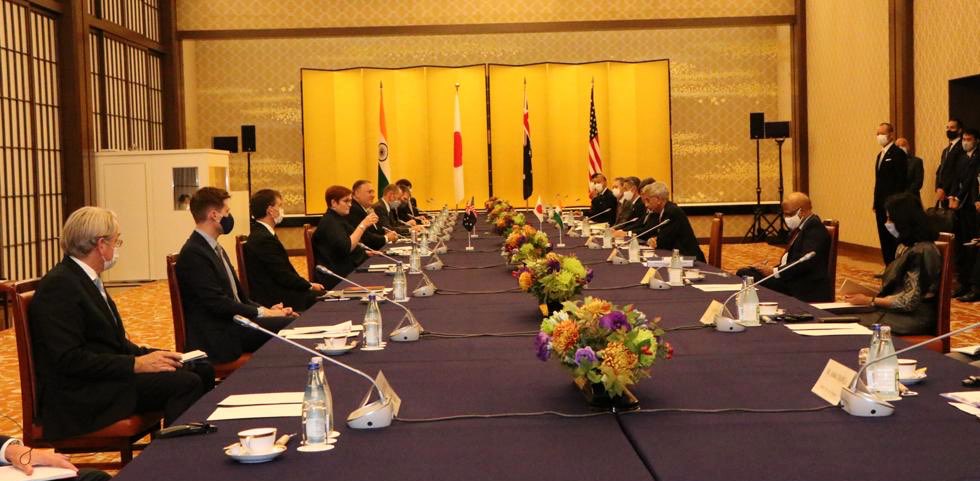

On the political front, the Foreign Minister-level meeting of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue or Quad in Tokyo on 6 October is a positive development, while Australia’s participation in the Malabar exercise would bring seamless coordination amongst the Quad countries. The Quad Plus, a conjectural group that would include Vietnam, S. Korea and New Zealand in addition to the four Quad countries, is being written about by analysts. Europe cannot be left out of this strategic engagement. It is an important market for Chinese goods. The UK and France would be natural partners for the Quad in Europe. They have strong seafaring traditions and capabilities. The UK has a long-term interest in the Indo-Pacific. It has strong linkages from its past with South and Southeast Asia, especially Hong Kong. Germany is another European economic power-house whose participation could be useful. The visit of Foreign Secretary Harsh Shringla to these countries at this juncture, even as countries in Europe are going into lockdowns, should provide the opportunity to highlight India’s concerns.

There is much that is happening on the India-U.S. front. The third edition of the 2+2 dialogue in the midst of a global pandemic, just a few days before the U.S. Presidential elections shows the seriousness of the two countries: India and the U.S. signed a landmark defence agreement, Basic Exchange and Cooperation Agreement (BECA) on October 27. This will allow the two countries to share high-end military technology, classified satellite data and critical information. There is obviously a cross-party consensus on India-U.S. relations and the signing of the long-negotiated BECA between the two strategic partners provides the framework to further boost future bilateral defence and military ties.

India is conscious that in this day and age, countries need to resolve their problems peacefully. India and China are nuclear weapon states. Both have strong defence capabilities. Chinese media sometimes refer to the 1962 India-China war in an effort to intimidate India. It would be a grave misjudgement on China’s part to equate today’s India with the newly independent nation of 1962. China should also bear in mind that a country that lacks the safety valve of democracy and needs the goodwill and markets of other countries for its own prosperity must respect the redlines of other countries and strive for peaceful coexistence. In an interdependent world, China needs the world, just as much as the world needs it.

(The author is former High Commissioner of India to the UK and was Secretary (West) in the Ministry of External Affairs, New Delhi. Views expressed in this article are personal.)