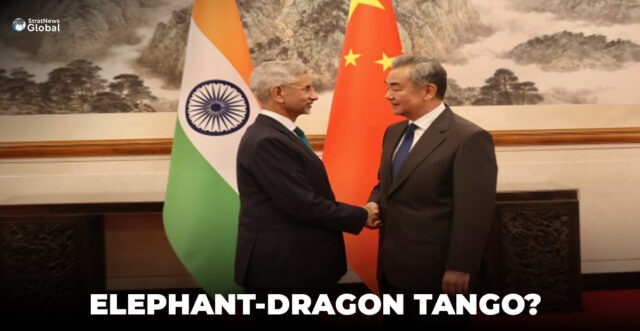

External Affairs Minister S. Jaishankar’s meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing on July 15 was the first direct engagement at that level since the bloody 2020 Galwan clash derailed bilateral ties.

Coming on the sidelines of the SCO foreign ministers’ meeting, the encounter was short but layered. Jaishankar conveyed greetings from India’s leadership and underlined the importance of peace along the LAC for any forward movement.

Xi, in turn, spoke of improving ties through “strategic guidance” and “accumulating positive energy,” a phrase that sounds pleasant but remains vague.

In an apparent reference to Beijing stopping the export of critical minerals, Dr Jaishankar stressed the need to avoid “restrictive” trade measures and “roadblocks” during his talks earlier with his Chinese counterpart Wang Yi.

In a post on X, Jaishankar said he also met International Department of the Chinese Communist Party Minister Liu Jianchao, with whom he “discussed the changing global order and the emergence of multipolarity,” and “spoke about a constructive India-China relationship in that context.”

The Global Times, Beijing’s unofficial mouthpiece, pushed the line that both countries are “exploring ways to turn the page” and emphasized that “the essence of China-India relations lies in coexistence and mutual success,” quoting Wang Yi.

But that same piece hinted at Beijing’s preferred framing: the burden of improvement lies more with New Delhi than with Beijing. It praised India for showing “pragmatism” and “restraint,” code for not pushing too hard on issues like Aksai Chin, Chinese infrastructure near Arunachal, or support for the Dalai Lama.

In a separate article, the Global Times leaned on the metaphor of a “dragon-elephant tango,” suggesting that two major civilizational powers—China and India—are finding rhythm despite past collisions.

But metaphors don’t erase realities. Roughly 60,000 troops remain deployed along the contested border. Multiple rounds of military talks have achieved tactical disengagement at some flashpoints but no strategic de-escalation.

China’s rapid infrastructure buildup near the LAC continues, while India has hardened its posture with more patrols and better logistics. Meanwhile, trust remains in short supply.

Chinese blocking of UN designations for Pakistan-based terrorists, continued surveillance of Indian Ocean activity, and the use of Bhutan and Nepal for strategic pressure are all part of the backdrop.

Even so, the tone of the visit marks a shift: less rhetorical heat, more diplomatic choreography. Since October 2023, a joint effort to reopen channels has brought back some basic functions. Border talks resumed, direct flights restarted in January, and cultural exchanges, including the Kailash Mansarovar pilgrimage—are on the table again.

But without movement on the deeper issues—China’s continued claim on Arunachal Pradesh, the unresolved standoff in Depsang, Beijing’s blocking of Indian media access and visa harassment, or the larger question of how India fits into China’s strategic vision for Asia—these diplomatic niceties won’t be enough.

Jaishankar’s visit signals that India sees value in engagement as equals. China, for its part, wants to stabilise ties with a major trade partner while keeping its military and territorial posture intact. The two can keep talking, but the question is whether talk will eventually lead to traction—or whether this dance is just for show.

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.