As Delhi gets ready to host the first meeting of the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) partner countries on August 5, a long-awaited opportunity has emerged to breathe life into what has so far remained a promising but stalled initiative.

Announced at the G20 Summit in New Delhi in September 2023, IMEC was envisioned as a transformative infrastructure and connectivity project linking India to Europe via the Arabian Peninsula. Now, with the first official gathering of stakeholders imminent, a policy brief authored by Col. Rajeev Agarwal (Retd) and published by the Chintan Research Foundation offers a detailed and clear-eyed set of policy recommendations to move this ambitious project forward.

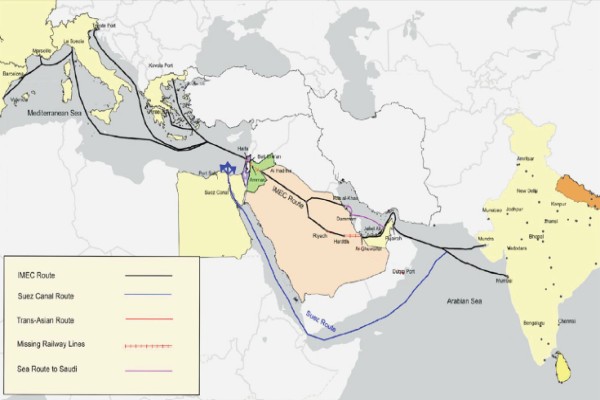

The brief describes IMEC as a multidimensional connectivity corridor encompassing maritime routes, high-speed rail, green hydrogen pipelines, digital cables, and energy transmission infrastructure.

Billed as a strategic alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, IMEC includes eight core partners—India, the U.S., UAE, Saudi Arabia, France, Germany, Italy, and the European Union—with other aligned countries like Jordan, Israel, Greece, and potentially Egypt and Oman playing vital transit or logistical roles. It has been positioned as a high-value, rules-based initiative focused on secure, sustainable trade and energy flows between Asia and Europe.

Despite strong diplomatic backing—evident in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 2025 visits to Washington and Paris and the European Commission’s emphasis on IMEC as a “modern golden road”—progress has been elusive.

The October 2023 outbreak of war in Gaza exposed the corridor’s vulnerability to geopolitical shocks and effectively derailed early momentum. As the Chintan report notes, the MoU signed at the G20 Summit envisaged a meeting of partner countries within 60 days, but that meeting is only now happening, nearly two years later.

Crucial implementation challenges persist. Over 600 kilometres of rail infrastructure connecting Al Guwaifat in the UAE to Haifa in Israel via Saudi Arabia and Jordan remain incomplete. Without integrated rail, customs, and security agreements—especially between politically sensitive links like Saudi Arabia and Israel—the project risks delays and inefficiencies. Bilateral efforts such as the India-UAE ‘MAITRI’ digital trade corridor are a step forward but insufficient to support IMEC at scale. A coordinated regulatory framework is still lacking.

Strategic contradictions are another concern. As first highlighted in an earlier StratNewsGlobal report, Haifa Port—a critical IMEC node—is operated by China’s state-run Shanghai International Port Group. This undercuts IMEC’s foundational premise of reducing strategic dependence on Chinese-led infrastructure models and exposes it to external influence in a project designed to enhance autonomy from Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative.

European involvement also remains fragmented. France, Italy, and Greece are pushing rival ports—Marseille, Trieste, and Piraeus—as IMEC’s primary European landing points. In the absence of a unified EU approach, the corridor’s integration into Europe’s existing rail and trade systems remains aspirational. With attention diverted by the war in Ukraine and rising defence expenditure, the political will to prioritise IMEC remains weak across much of Europe.

To address these vulnerabilities, the Chintan report proposes a suite of realistic and actionable steps. First, it recommends that India take the lead by establishing an IMEC Secretariat in New Delhi, drawing from its experience anchoring the International Solar Alliance. A central coordinating body with representation from all partners could help navigate political complexities, resolve technical disputes, and accelerate decision-making.

Second, the report calls for complementary alignments to the core IMEC route—particularly via Egypt and Oman. Egypt’s Suez Canal Economic Zone, multiple operational ports, and extensive green hydrogen infrastructure make it an ideal logistics hub and staging point for IMEC’s Mediterranean leg. Oman’s Duqm Port, located outside the Strait of Hormuz, provides an alternate maritime route less vulnerable to regional tensions. Both countries maintain neutral foreign policies, which could enhance IMEC’s long-term viability.

Third, the report places heavy emphasis on integrating energy and digital flows into the corridor. A proposed 700-km undersea High-Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) link connecting India to the Gulf could enable real-time cross-border energy exchange, especially in solar power. This would align closely with India’s One Sun, One World, One Grid (OSOWOG) initiative. The undersea cable could also carry data and hydrogen pipelines, creating a multi-utility conduit across continents. However, regulatory convergence in power-sector laws and standards across IMEC countries is essential for this vision to materialise.

On the economic front, the report points to India’s urgent need to scale up its manufacturing base, currently just 3% of global output, compared to China’s 30%. Without expanding its industrial corridors and logistics backbone, India risks becoming a transit country rather than a value-adding hub. IMEC must be tied into domestic infrastructure development, particularly through linkages to India’s Northeast and the Trilateral Highway extending to Thailand and ASEAN.

Financing, perhaps the biggest uncertainty, remains unresolved. The Chintan Foundation recommends the creation of an IMEC Funding Secretariat to coordinate inputs from sovereign wealth funds (especially from Saudi Arabia and the UAE), multilateral development banks, and private investors. A hybrid approach would allow national governments to fund internal infrastructure while international institutions support shared or cross-border components like undersea cables or transnational rail.

Ultimately, the brief underscores a central truth: while geopolitically driven, IMEC must make economic sense to succeed. The comparison with the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC)—which took nearly 24 years to materialise—is instructive. IMEC can and should move faster, given the stronger political alignment and economic heft of its partners. But that requires institutional capacity, realistic timelines, and above all, a clear and coordinated implementation strategy.

As India prepares to host the first IMEC partner meeting, the opportunity exists to reset the narrative—from promises and press releases to plans and performance.

The Chintan Research Foundation’s policy recommendations provide a credible roadmap. But unless the corridor’s strategic contradictions are resolved, its financing structure clarified, and its regional linkages secured, IMEC risks becoming another grand vision weighed down by geopolitics and inertia.

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.