China’s decision to push ahead with constructing a massive dam on the Yarlung Tsangbo (as the Brahmaputra is known in Tibet) near the Great Bend — where the river curves sharply before entering India — has raised some concerns in India.

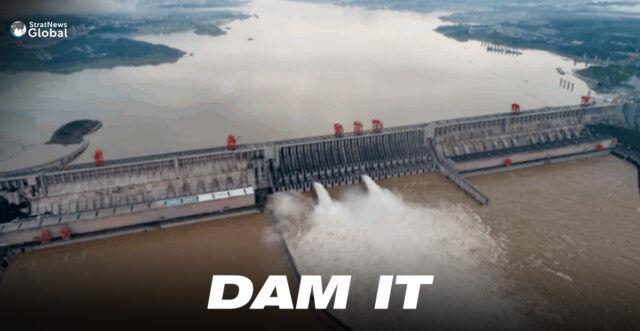

The project, greenlit under China’s 14th Five-Year Plan, is reportedly designed to generate 60 GW of hydropower, nearly three times the capacity of the existing Three Gorges Dam. If completed, it would be the largest hydropower project in the world by output.

The move, formally marked by the start of construction in July 2025, was announced by Chinese authorities as a major milestone in national infrastructure development.

According to a July 22 report by Al Jazeera, China has officially begun work on what it calls the world’s largest hydropower dam in Tibet’s Medog County.

The project, part of China’s broader push for clean energy and carbon neutrality, is also seen as a strategic initiative to develop the last major untapped river basin in the country — barely 30–50 km from the Indian border, in one of the most ecologically and geologically sensitive zones in Asia.

A senior Indian specialist on water resources has pointed out that 28 dams have already been proposed by China along the Yarlung Tsangbo, several of which — like Zangmu (completed in 2015), Dagu, and Jiacha — are run-of-the-river schemes. These involve minimal storage and do not significantly disrupt downstream flow. In contrast, the Great Bend project is designed for water diversion and long-term storage, potentially depriving India and Bangladesh of critical water volume.

The same expert underlines that this stretch contributes around 50 BCM out of the 115 BCM of annual water flow at India’s Tuting station — accounting for 43% of Siang flow and over 60% of the Brahmaputra’s total volume at critical points. With China controlling this upstream volume, it gains significant leverage over South Asia’s water security.

China has presented the Great Bend project as part of its effort to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060. This aligns with the rhetoric used by President Xi Jinping during the 7th Tibet Work Forum in September 2020, where he declared that “protecting the ecology of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau is the greatest contribution to the survival and development of the Chinese nation.”

Xi’s “Ten Musts” for Tibet included environmental sustainability and even called for “systematic plans and engineering measures for protection, restoration, and governance.” Yet this very region — Pemakoe, adjacent to Arunachal Pradesh — is being targeted for a project that risks triggering devastating seismic and hydrological consequences.

The contradiction is glaring. On one hand, a vision of Tibet as a “national ecological civilization highland”; on the other, the construction of a mega infrastructure project in one of the most landslide- and earthquake-prone areas in Asia.

The region’s seismic history raises serious questions. The 1950 Rima earthquake, with its epicentre just north of Arunachal Pradesh, caused catastrophic flooding and widespread devastation. As The Times of London reported, the Brahmaputra ran black with sulfur, dead fish, and carcasses of wild animals. It took weeks for the full scale of the destruction to become known.

More recently, in November 2017, a 6.9 magnitude earthquake near Mt Namcha Barwa triggered massive landslides that blocked the Yarlung Tsangbo in several locations. The Siang River in Arunachal Pradesh turned black, alarming residents and prompting media investigations. According to SANDRP and Arunachal Times reports, three natural dams were formed over a 12-kilometre stretch, with flood risks looming for downstream Assam.

Then, in October 2018, a second landslide at Pe Village in Mainling County — just upstream of the proposed HPP site — again blocked the river. China was forced to notify India, triggering emergency protocols in Arunachal Pradesh.

These incidents underscore the fragility of the terrain and the unpredictability of tectonic activity in this zone. The prospect of a mega dam here, therefore, is not just an environmental gamble — it’s seismological negligence.

Compounding these risks is China’s decision to terminate the bilateral hydrological data-sharing MoU with India in June 2023. China now demands reciprocal data, reducing India’s access to critical flood-season information. In a region with such a volatile natural record, this loss of transparency is deeply worrying.

India’s analysts warn that beyond power generation, China’s real motive may be geopolitical leverage. With the Brahmaputra forming a crucial water source for India and Bangladesh, Beijing could influence water availability — or engineer sudden releases.

The proximity to Arunachal Pradesh, which China claims as “South Tibet,” adds a further layer of strategic intent.

China’s Great Bend hydropower project is an engineering feat, but one built on a foundation of risk. Its construction in an earthquake-prone zone contradicts the country’s own ecological proclamations. Its potential for diversion threatens the hydrological integrity of South Asia. And its opacity risks turning a regional resource into a weapon of statecraft.

Whether China will ever reconcile its green ambitions with ground realities remains to be seen. What is certain, however, is that the costs of miscalculation will not be borne by China alone, but by the millions living downstream — in India and beyond.

Part II : China’s Mega Dam And India’s Asymmetric Challenge

Part III: Strategic Waters: India’s Dam Dilemma in Arunachal Pradesh

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.