The India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), announced with much fanfare at the G20 Summit in New Delhi in September 2023, promised a bold new model of transcontinental connectivity.

Less than two years on, that promise remains largely unfulfilled.

A recent conference organised by the Chintan Research Foundation, featuring diplomats, academics, and industry leaders, underscored just how far IMEC is from moving beyond its PowerPoint phase.

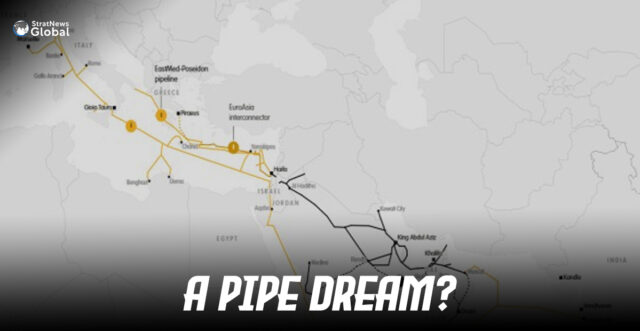

At its core, IMEC is envisioned as a multi-modal infrastructure network—combining sea routes, overland rail, undersea digital cables, energy pipelines, and renewable electricity transmission grids—linking India to Europe via the Arabian Peninsula.

Yet as detailed in the conference proceedings, nearly every element of the plan remains mired in delay, uncertainty, and geopolitical contradiction.

The Gaza conflict, which erupted just weeks after the project’s launch, has become a major stumbling block. Speakers repeatedly flagged the war as a stark reminder of the fragility of West Asian geopolitics. The report bluntly states that progress on IMEC remains “susceptible to geopolitical turbulence,” and that the corridor’s advancement is vulnerable to “episodic disruptions” until there is some resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

In fact, a foundational meeting of IMEC partner countries—mandated within 60 days of the G20 MoU—has yet to take place. No feasibility studies have been released, no funding mechanisms defined, and no timelines agreed upon. Meanwhile, regional power shifts, unresolved rivalries, and diplomatic mistrust continue to undermine the coherence of the project.

The project’s North Corridor—traversing the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan and Israel—faces particular scrutiny. The absence of formal customs and security agreements, particularly between Saudi Arabia and Israel, has left the corridor exposed to political stalemates. Even basic operational questions—who will control border security, what regulatory frameworks will apply, how cargo will be cleared—remain unanswered.

Even more awkward is the role of China. The Port of Haifa, a critical trans-shipment node in the IMEC plan, is currently operated by the Shanghai International Port Group—a Chinese firm. As one speaker noted, this creates a “strategic contradiction” at the heart of a Western-backed initiative meant to serve as a democratic, values-based alternative to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The contradiction is especially pointed given India’s and the West’s growing unease with China’s expanding footprint in global infrastructure.

This tension is not theoretical. The Chintan report highlights the need for Israel to “take the lead” in resolving the Haifa port issue, acknowledging that Chinese control of a key node could compromise the strategic independence of the corridor.

On the logistics front, IMEC faces steep structural barriers. While it may shave roughly three days off the Mumbai-to-Europe shipping route compared to the Suez Canal, this minor time advantage is undercut by the complexity of trans-shipment across politically sensitive and poorly integrated regions.

A standard shipping route from Mumbai to Piraeus via Suez covers 7,637 km in about 12 days. IMEC’s proposed route shortens this to about 6,600 km, but adds layers of regulatory and logistical friction.

Critically, the report notes that rail freight costs 2.5 times more than ocean freight, and each trans-shipment adds cost and risk. The corridor’s hybrid model—60% sea, 40% overland—introduces operational inefficiencies that make its advertised cost and time benefits highly questionable. Without regulatory harmonisation and massive capacity upgrades, the corridor may end up slower and more expensive.

One glaring example: a single large container ship carries 20,000 TEUs, while a train can carry just 260. To match that, over 75 trains would be required. Current capacity on the UAE’s Etihad Rail network is just 1.1 million TEUs annually—IMEC would require a 35-fold increase.

Where IMEC does offer a distinctive edge is its integration of renewable energy and digital infrastructure. The inclusion of green hydrogen pipelines, high-speed data cables, and undersea electricity transmission links sets it apart from traditional connectivity models. India has committed $2.5 billion toward building a green hydrogen ecosystem, and companies like Adani and ReNew are positioned to play key roles.

The corridor aligns with India’s One Sun, One World, One Grid (OSOWOG) initiative, enabling real-time cross-border solar energy sharing. The planned 700-km undersea High-Voltage Direct Current (HVDC) link is technically feasible and could unlock energy trade between India and the Gulf. But again, the regulatory frameworks and multilateral coordination needed for such innovation remain absent.

Perhaps the most fundamental challenge is funding. While the report recommends creating an IMEC Funding Secretariat and engaging sovereign wealth funds and multilateral development banks, no such mechanisms currently exist. Private sector involvement is acknowledged as essential, but without clarity on risk-sharing or returns, investor appetite remains muted.

A proposed division of responsibilities—where each country develops its domestic ports and logistics infrastructure, while high-cost elements like undersea links are jointly financed—remains theoretical.

As the Chintan report makes clear, IMEC is not without merit. It reflects India’s rising global profile, its deepening ties with West Asia, and its ambition to be a hub for sustainable infrastructure.

But vision alone cannot move cargo—or geopolitics. Until there is hard commitment from partner countries, funding clarity, and institutional backing, IMEC remains more symbol than substance.

In a career spanning three decades and counting, Ramananda (Ram to his friends) has been the foreign editor of The Telegraph, Outlook Magazine and the New Indian Express. He helped set up rediff.com’s editorial operations in San Jose and New York, helmed sify.com, and was the founder editor of India.com.

His work has featured in national and international publications like the Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, Global Times and Ashahi Shimbun. But his one constant over all these years, he says, has been the attempt to understand rising India’s place in the world.

He can rustle up a mean salad, his oil-less pepper chicken is to die for, and all it takes is some beer and rhythm and blues to rock his soul.

Talk to him about foreign and strategic affairs, media, South Asia, China, and of course India.