When Ukrainian Leniie Umerova crossed into Russia in late 2022 to visit her ailing father in their native Crimea, she was detained and subjected to nearly two years of what she calls a “carousel” of charges, solitary confinement, and prison transfers — an ordeal that, for the 27-year-old Crimean Tatar, crystallised the deep generational trauma of her community since Russia’s 2014 annexation of the Black Sea peninsula.

“It was very difficult because I was constantly alone in my cell and they (the Russians) periodically tried to feed me their propaganda,” said Umerova, who initially faced administrative charges and later accusations of espionage, which she denied.

Umerova had grown up listening to her grandmother’s stories of how in 1944 the family, along with hundreds of thousands of other Crimean Tatars, were deported to distant Central Asia on Soviet dictator Joseph Stalin’s orders for alleged collaboration with the Nazis, even though many Tatars including her great-grandfather were fighting for the Red Army.

Thousands died from disease or starvation, and the Tatars were only allowed back to Crimea in the 1980s. Now Umerova fears that Crimea, as part of a final Ukraine peace deal, could be recognised as part of Russia – a scenario that the Trump administration in the United States has signalled is possible.

“For so many years now, the same enemy has been doing evil to our family,” Umerova said. “If we don’t fight now and overcome this, where are the guarantees that my children or my grandchildren won’t get the same (treatment)?”

Always before her is the example of her grandmother, who refused to speak Russian when Umerova was young and immersed the family in Tatar culture and language.

“Whatever happens, we must return to Crimea,” was the message.

Umerova returned to Kyiv after being released by Russia in a prisoner swap last September, and despite her suffering, she remains hopeful that the Tatars, a Sunni Muslim Turkic people, will one day be able to live freely again in a Ukrainian Crimea.

“Every day, every year… you live with the dream that now, now, now they will deal with this one thing and return Crimea… And so it will be, I am 100% sure of this,” she added.

Russia Won’t Budge

But Russian President Vladimir Putin has said that any peace settlement for Ukraine must include recognition of Russian sovereignty over Crimea and four other Ukrainian regions.

Moscow denies Kyiv’s assertions that it is violating the rights of Tatars and other people in Crimea, which it says is historically Russian.

According to the Ukrainian President’s Mission in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea, some 133 Crimean Tatars are currently illegally imprisoned by Russia. Russia’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to a Reuters request for comment.

“To give (Crimea to Russia) is to simply spit in their faces,” Umerova said of those detained Tatars and of the tens of thousands who continue to live in occupied Crimea.

Russia’s Foreign Ministry did not respond to a request for comment on this article.

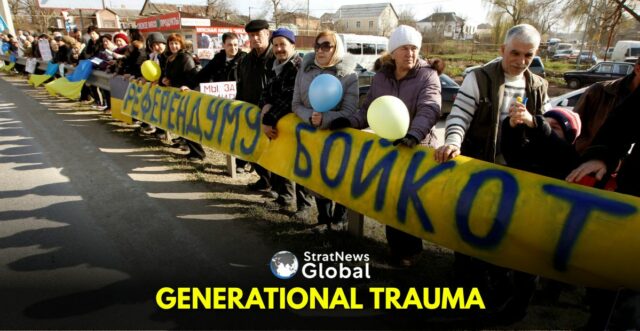

At the time of Russia’s annexation, Crimean Tatars accounted for around 12% of the peninsula’s population of some two million. They rejected Russia’s occupation and boycotted a referendum at the time, and community leaders estimate that some 50,000 have left since 2014, though most have remained there.

Crimean Tatar rights activist and journalist Lutfiye Zudiyeva, who lives there, said Russia had subjected her community to what she called “active assimilation”.

“Of course, today in Crimea you can sing in Crimean Tatar and dance national dances, but the people have no political agency,” she said.

Crimea is internationally recognised as part of Ukraine by most countries, but U.S. President Donald Trump told Time magazine in April that “Crimea will stay with Russia”.

Under peace proposals prepared by Trump’s envoy, Steve Witkoff, the United States would extend de jure recognition of Moscow’s control of the peninsula. However, the two sides have made little progress in peace talks since April.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy is trying to resist Trump’s pressure to cede territory to Russia as part of any peace settlement, and he has cited Umerova’s case as an example of what he says is Moscow’s repression of the Crimean Tatars.

For Ukrainian singer Jamala, who won the Eurovision Song Contest in 2016 with her song “1944” about Stalin’s deportations, any talk of legally recognising Crimea as Russian is “insane”.

“If a country like America says ‘it’s no big deal, let’s just forget about it and move on’, then there are no guarantees in the world,” Jamala told Reuters.

(With inputs from Reuters)